April 6, 2018

10 Questions for Artist Brett Goodroad

The rising Califiornian painter discusses art, literature and truckin'

Brett Goodroad (b. 1979) is an artist and painter based in San Francisco. Born and raised in rural Montana, in 2012 he received the Tournesol Award, overseen by Sausalito’s Headland Center for the Arts. The Award recognises one Bay Area painter each year and financially assisted Goodroad and gave him studio space, allowing him to develop his distinctive, figurative, abstract style. He has since exhibited extensively in California as well as New York and Vermont. His monograph, A Sequence in Love was published in 2016 and in May he will be exhibiting at the Phoenix Gallery in Brighton as part of the Brighton Festival.

For some years Goodroad has partially funded his existence by driving trucks for Veritable Vegetable, an organic vegetable distributor. theartsdesk caught up with him two days into a New Mexico run. He honks his horn to show that he is truly on the highways of the American West.

THOMAS H GREEN: How did you get involved in the Brighton Festival?

BRETT GOODROAD: David Shrigley [Guest Director of Brighton Festival 2018] asked me to show. I met him up at the Headland Center for the Arts in 2012. We’ve been in touch since. You could say we’re pen pals, I guess. You know, he seems to really like my work but he’s not the kind of guy who showers you with praise. He’s always just been a really good person as far as all artists I’ve known are concerned.

Are you coming over for your exhibition in Brighton?

I’ll be over for the opening. I’ve never been to Brighton. I’ve never even been to the UK. There are lots of things I’d like to check out. I’d like to see the Lake District, then over to Italy for a bit, and fly back home from there.

I hear you spend your time in the cab of your truck listening to audiobooks. What are you listening to at the moment?

Well, the one I’m kind of circling round right now is A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry. It’s about India over a couple of different time periods. I get through a lot of stuff. My education in Montana wasn’t that involved in literature. Of course, I had kind of a religious background so I had a lot of interest in language in a quizzical fashion, finding meaning out of language. But people like Marcel Proust were an enigma to me. Being able to listen to that aloud gave me some access into how to actually read the sentences. Same with James Joyce. I didn’t know how to get into it until I started listening to it. The road, in more than one way, has been very profitable to my practice as a painter.

Are your figurative abstract paintings flavoured by the endless American landscapes you see on the road?

I think what you’ll see in the exhibition is definitely landscapes but I’ve never been somebody who’s very direct, not literally making paintings about truck driving or landscapes. All this time behind the wheel, especially in the deserts of the south west, I’ve definitely learnt how to create space in all my work.

And you do your painting in your backyard?

All the paintings are done in my backyard. In San Francisco we get a lot of fog from the ocean which works really well for painting. The light is amazing, glowing light that comes through the clouds. It’s beautiful, really perfect for painting. I have a small paper studio 10 blocks away from where I live. This lady who frames my work lets me use it for printmaking and actually all the work for the Festival is going to be done out of there. I’ve been in that space for the last six years and even that has had an influence on my work. It’s moist and I’ve had to battle mould there. A lot of influences popped up into my work without my knowing.

Have your family been supportive of your artistic career?

You know they never really had an artist in the family so they’ve never really known what to do with me. My dad did OK, he went into the business of agriculture, he grew up on a farm, all my uncles are farmers, my grandfather was a famous farmer who went to Russia and taught a bunch of people how to grow corn. The one thing I can say about having a family that’s more blue-collar is I didn’t have a lot of pressure on me to go to the right school, they were just happy that I could make a living. They never really understood my work but they’ve never been against it.

Do your trucking friends know about your art career?

When I’m out here I don’t really talk about it unless they bring it up. When I’m out on the road going to cold storages and places where you end up waiting for hours for asparagus or broccoli, I might run into another truck driver. I meet them wherever they’re at...

I was thinking more of your associates at Veritable Vegetable...

They’ve been incredibly supportive. They give me my schedule. I work a five-day run, then nine days off, and now my art career’s been starting to make more money. It’s a woman-run company out of San Francisco that’s been supporting sustainable agriculture since ’74. They’re actually one of the main cornerstones of the organic movement that brought it out of California in the Sixties and Seventies, so they’ve been an inspiration too. They’ve really grinded it out, a totally woman-run company coming into the totally male world of trucking. I’m really proud to work for them. I’m incredibly lucky to have landed where I did. When I got done with grad school I was working for a gallery. I got fired from that for, like, the dumbest reason. I had the truck-driving experience from when I was growing up. I worked on harvest runs when I was 17, travelled up from Texas to Canada, harvesting wheat, barley and all these small grains, so I had all that experience. I knew that I could drive trucks but most people I could drive for I’d be out on the road six days, maybe a day off, six more days, then another day off, but by some little miracle I started working for these ladies. I can’t say enough about them, actually. They’re really stoked on the Brighton Festival thing.

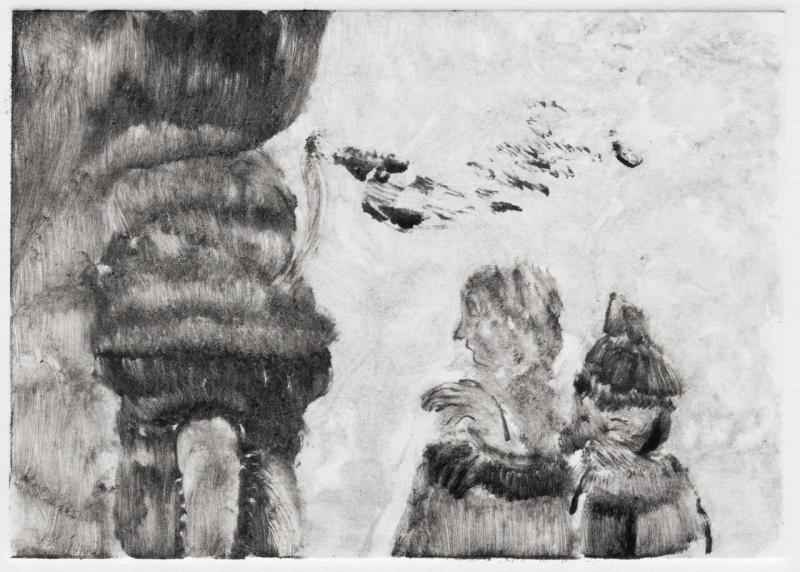

Tell us about Arrival, your monotype that’s being used to promote the Brighton exhibition [and which readers can see at the head of this interview].

Well, there are a few things going on. It’s not direct but immigration, all the things happening in Europe and the States, but not like I’m actually putting symbols in there. Those two figures are travelling from the East to the West. If you look, there’s a really tiny gate. It’s got these pillars and a small doorway. The figure in the front is actually putting his hand out and he’s in a bucket. I imagine them both kind of in the water, floating across the water. The figure next to him, in my mind, isn’t necessarily a child but a strange animal-like, bird-like figure that’s just sneezed and is wiping his nose with a wing. Another thing that happens in my work a lot is figures turn into animals. All the work in Brighton is going to be black and white. That image gives some sense of the exhibition.