November 17, 2017

Seth Koen @ Gregory Lind

by David M. Roth

You’ve heard the old saw about sculpture being drawing in space? Seth Koen takes it to heart. His “lines” – pencil-width lengths of wood – might well define the far end of post-minimalist austerity were it not for the artist’s habit of carving them by hand and wrapping them in crocheted cozies. Out of these seemingly opposite approaches, one rooted in craft, the other in high Modernism, come surprises, the biggest of which is how, with the humblest of means, Koen is able to transform our perception of matter and volume.

For Koen, less has always been more; but with Waver, his sixth exhibition at Gregory Lind, the subtractive impulse, long in evidence, has clearly come to the fore. Where in the past he wrapped long dowels in yarn to create bulbous shapes reminiscent of aquatic plants, and worked slabs of raw wood into even weirder forms, he now seems focused on whittling his shapes down bare essences. Imagine details of Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings replicated in three dimensions and you’ll get a fair idea of Koen’s approach. Each piece in Waver is essentially a micro-installation, designed not so much to stamp the identity of a specific object in memory, but to activate space in ways that, to paraphrase Duchamp, allow viewers to complete the work in the act of looking.

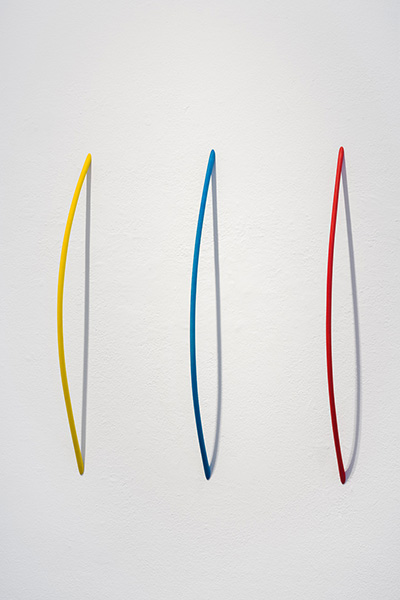

First Things First, appears to be a deadpan statement: nothing more than three colored pieces of wood set against a wall, their curves facing outward. But in the side view everything shifts. The wall and the shadows become structural elements, and flatness gives way to dimensionality, proffering the illusion of crossbows mounted side-by-side. Wired Weird, a pair of curved sticks wedged between the floor and the wall with no apparent means of support, also elicits a long and inquiring look, as does The Humors 2, a horizontally mounted length of wood whose crisscrossing shadows, generated by a V-shaped kink at the center, call to mind a flat-lined EKG. All three are fine examples of how Koen builds compositions out of the immendiate environs, doing so by playing object against void and by using shadows and architectural details as key structural elements.

Other works reminiscent of things seen in earlier exhibitions round out the show, injecting into it qualities not typically associated with Minimalism: humor and nature-based lyricism. Layed, a long, thin slab of raw wood about the width of a necktie, drapes across a wall partition, calling to mind Dali’s melting wristwatches. Whipsmart, a doubled-over line in space that stands seven-and-a-half feet tall, reminds me of the crook-necked tropical birds Audubon painted. Seamlessly beveled from “tail” to tip, it was carved from single chunk of wood, a mindboggling labor of love.

Koen grew up in rural Maine, the son of back-to-land parents who made their own clothes, baked bread and farmed. Early in his career, the Masschusetts artist served as Ron Nagle’s studio assistant, and from Nagle, arguably the world’s most imaginative ceramic sculptor, Koen seems to have acquired a taste for hybridity along with an abiding sense of what can be wrung from mere lines.

I don’t recall Nagle’s exact words on this topic, but the essence what he said was: give me a line and I’ll give you the world. Koen, though far less flamboyant, appears to be walking a similar path.