May 13, 2016

Tom Burckhardt @ Gregory Lind

by David M. Roth

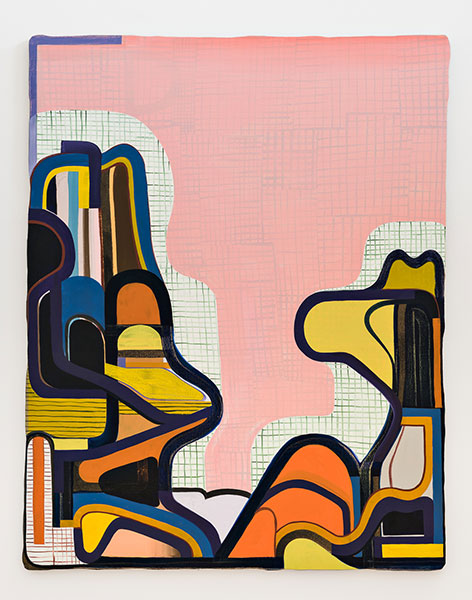

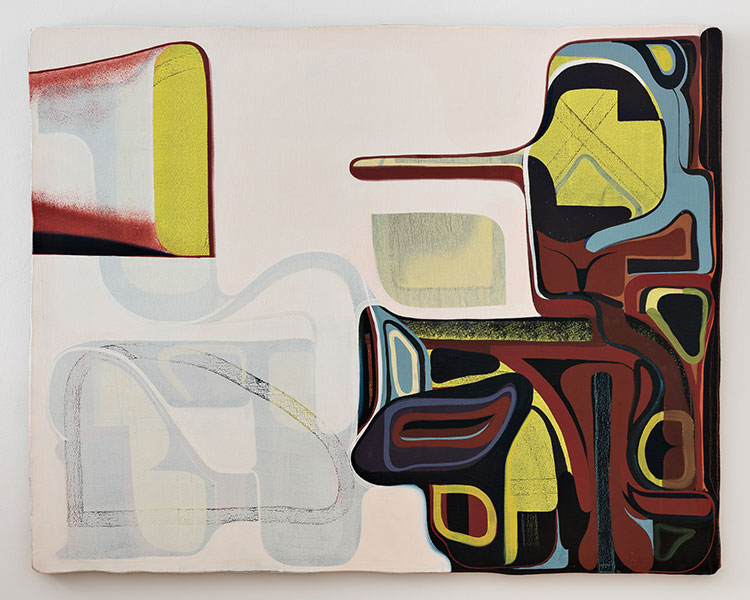

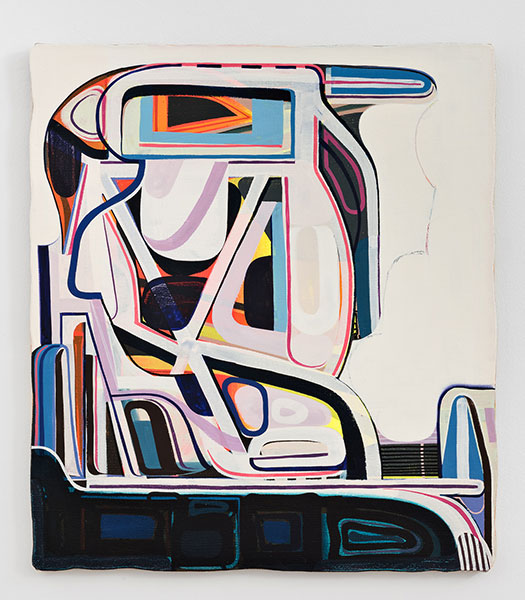

Gawky, totemic, retina-tingling and multi-layered, Tom Burckhardt’s paintings don’t just split the difference between representation and abstraction; they render such distinctions null and void. In so doing they’ve catapulted the New York artist to the front rank of contemporary painting. A quick glance at the eleven works that comprise his current show, City Slang, indicates a synthesis of many things: the tribal-influenced abstract painting of Steve Wheeler (1912-92), the comic figuration of Philip Guston and the Surrealism of the Hairy Who painters, Jim Nutt and Karl Wirsum. One can also detect traces of Carol Dunham and even stronger hints of the Brazilian landscape architect/painter, Roberto Burle-Marx (1909-94), whose innovations in tropical design are now on view in a career retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York. Burckhardt, without appearing derivative, works these influences into collisions that suggest body parts and landscapes. While we’re conditioned to think that painting should be one thing or the other, representational or abstract, Burckhardt refuses to submit to any singular approach or orthodoxy. Instead, he operates from the position that doubt and ambiguity are central to his working process.

To lure us into that zone, Burckhardt fills his paintings with biomorphic shapes that border on caricature, faintly and sometimes strongly evoking the iconography of Pacific Northwest Native American tribes, the Tlingit in particular. Saint Skeptic, one of the two largest (48 x 60 inches) paintings in the show, contains forms that suggest tongues, buttocks, testicles and arterial networks, as well as an elongated “nose” near the top that may remind you of Poor Richard, Guston’s 1971 book-length send-up of Richard Nixon.

Similar elements combine to form strong allusions to farmscapes and cityscapes, sometimes in the same canvas, as in the title piece, where ovoid shapes crisscrossed by diagonal lines make for ponds, crop rows and winding waterways. Conversely, you can look at these and other paintings, like Vertazontal, and just as easily imagine urban/industrial sources. The pictorial elements that generate these impressions are, for the most part, densely clustered in the corners of the canvases. Each group is offset by voids – scrims, essentially, of negative space — through which vestiges of earlier compositions peek out from below the surface — an indication of the complex process by which Burckhardt completes a painting.

His off-kilter compositions, found in the moment of their creation, fully command the space they inhabit. Part of their strength rests with how the artist deploys strong and sometimes clashing colors. In City Slang, for example, acid yellows, greens and oranges play hard against swatches of fuchsia; while in Sneaker, shades of salmon battle for primacy against blacks, cerulean and cobalt blues, violet, maroon and a host of neutral colors.

The tensions are eye-grabbing. When it comes to paint handling, Burckhardt leans toward flatness. Yet between the surface and the sometimes-visible weave of painted linen there are plenty of painterly effects, evidenced in washes, drips and semi-opaque sections where different layers intermingle. Burckhardt isn’t much moved by the hands-off ethos of Postmodernism; he values labor and hard-won results too much for that. In that regard, he can also be positively linked to the LA painter Alex Couwenberg.

Burckhardt has long spoken of a desire to transform painting. One of his strategies is to alter the shape of his canvases by carving the edges of his frames into undulating curves, around which he wraps linen painting surfaces.

This may at first seem insignificant, but the impact, after prolonged viewing, shifts. In certain instances, where the painted parts come close to abutting the edges, the effect can be mildly gyroscopic, akin to the grind of tectonic plates. As such, Burckhardt’s paintings occupy more visual space than their modest scale might otherwise allow.

Here it’s worth noting that for many years the artist worked as a studio assistant to Red Grooms, a painter known for extracting great humor (and pathos) from warped spatial perspectives, mostly of scenes set in New York. Apart from how they pack imagery into their paintings, the two artists would appear to have little in common. What they do share is a desire to transform the way we see. By referencing and reinterpreting historic tropes of representation and abstraction, Burckhardt upsets the impressions we take from first glances.