May 3 2013

Tutubi Plaza

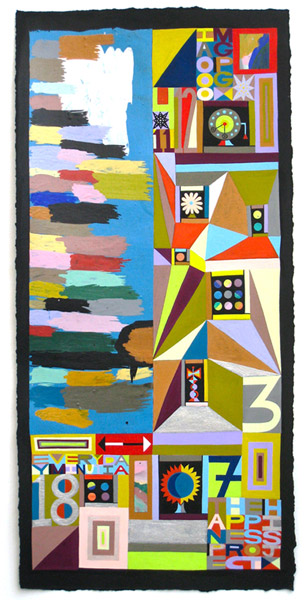

"Happiness Project"

"Optimist Club"

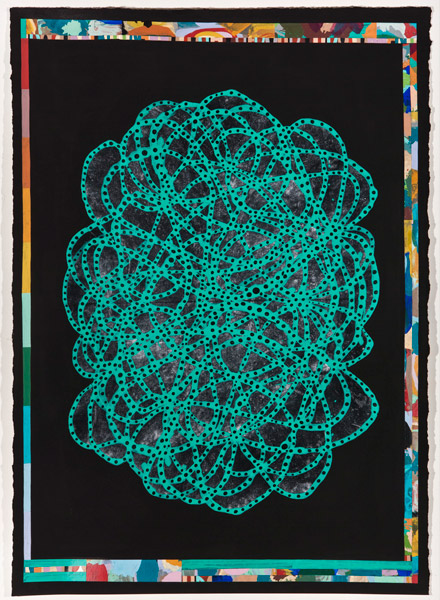

"Green Knot"

Jovi Schnell on Her S.F. Street Art, Rolling Dice, and Her "Hippie" Upbringing in Arkansas

It's hard to resist Jovi Schnell's new paintings, which are like mazes full of eye candy. The paintings are on display at Gregory Lind Gallery (49 Geary St.) through June 1, and they're a stimulating introduction to a San Francisco artist who's exhibited her work for two decades. You can also find Schnell's art on the pavement of Tutubi Plaza, an area near Sixth and Mission streets that the San Francisco Art Commission transformed in 2011. Schnell, 42, is an adjunct faculty member at the California College of Arts and a visiting lecturer at the San Francisco Art Institute (where she got her undergraduate degree in painting). She recently spoke to SF Weekly about her street art, her new exhibit, why dice influence what she paints, and how someone who grew up in a hippie environment in Arkansas made her way to San Francisco.

In 2011, the San Francisco Art Commission chose your art to beautify the newly named Tutubi Plaza. It's formerly run-down area on Russ Street between Natoma and Minna, and your artwork, Evolves the Luminous Flora, became the central part of the asphalt there. For the first time, people could walk on your art.

The Art Commission was trying to improve the neighborhood, and they wanted to bring an artwork to it. Every now and again, I'll ride my bike by it. I don't know if the project set out what it had intended to do. You never know with these projects, which take on their own life. Tutubi Plaza is a block from Sixth Street. You're not going to displace that reality by putting down an artwork. I remember going by it in the first couple of months. I sat there and had lunch from time to time, just to check it out. Occasionally, I would see a kid pointing at the flowers and the turtle. I was like, "Oh, good." And then I'd see someone doing their thing - and, obviously, they'd been doing it for the past 48 hours - and they'd say to me, "Isn't this beautiful - it's so nice!" It's a very mixed area.

The Art Commission said they chose your work partly because it appeals to kids. Picasso talked about how artists should try to paint as if they were children - to be in that unencumbered zone of creativity. Do you have a secret approach to art?

I take play pretty seriously, and experiment in the studio. I always try to discover new ways of combining things and saying them in a different way. It probably goes back to early childhood influences, too. I went to Montessori schools, where play and discovery methods and this experimental model was put before us - to go with what you're interested in and play with it and learn about the world through hands-on play. That extended into my public education, where I was with this batch of kids that was an experiment for this open-air classroom without walls, which encouraged children to also follow their individual interests. I can tell I wasn't in the math section that much (laughs). I was a single child who grew up in this back-to-the-land hippie spirit of the boomer generation. So nature was definitely worshipped and I was playing in it a lot. That's continued on.

So, the hippie spirit was alive and well in Arkansas in the 1970s?

Yeah. I was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, and we lived in Little Rock and then moved to Fayetteville and then eventually moved into the sticks, and tried to live the dream. I remember being in marches holding signs with emblems on them that I didn't quite know, but I knew they held power. The early influence of the kindergarten and this climate primed me for art school, right? (Laughs.)

Your new paintings at Gregory Lind Gallery are self-contained worlds full of curious shapes. The colors are especially inviting. You must have been in a good mood when you drew, say, the appropriately named Optimist Club or Honeycomb Hideaway.

I use the whole spectrum of color. For this body of work, I tried to expand my color palette by seeing what would happen if I worked with a collection of text and words that I've scribbled in my notebooks over the years. At one point I said, "This is good stuff -- why isn't it in the work?" It was kind of a diary. I thought it'd be interesting to see what would happen if I would randomly pick one of these words from what I was calling my "Brain Dump." It captured something I heard throughout the day -- something a friend said, something I overheard at a bar, something on the radio, something I'd see on my way walking to the studio. I just wanted to try and get that language into the work. For instance, there was an acronym I heard at one point, like IBGYBG, which was day-trading for, "I'll Be Gone You'll Be Gone." Also, I was teaching Color Theory, and I thought it'd be interesting to take the word or phrase and plug it into an online open-source palette generator, and see what happens when I plug in "Globe." Sure enough, all of these color palettes that had been uploaded online from designers and artists came up.

You also used dice, right? How very random.

I worked with a 20-sided die for generating the color palettes. The Brain Dump initiates the piece. The numbers in that show up in the work correlate to the rolling of the die. When I landed on No. 20, that was peacock blue. And that prompted me to roll a smaller die. I'd then record the number of the face of the die. It was, "work with restraint," then I get a selection. And I'd painstakingly color-match the palettes that I selected from what came up from what the word called out. I did tend to go with more full-spectrum -- red, orange, yellow, green, blue, purple. There was a mother color that I'd use to hold the whole thing together, and that was this peacock blue to line all the colors. I set up a system where I'd work left to right, roll the die, which would call out the color number, and I would paint that color. Then I'd flip the paper vertically, and do the same thing. It was a process of setting up this restraint and rules would rub up against the way the thing was being built.

A few years ago, one of your fans lauded a work of yours called Avenue of Eden, saying that, "I'm pretty sure that Jovi Schnell has made the female reproductive system look like the prettiest thing I ever saw. Part mechanical, part flora, part I don't know what, Schnell's paintings, illustrations and collages use rainbows of colors and mix geometric shapes with organic ones to create images that are pretty much amazing."

It's the "I don't know what" that I love. The painting is my interpretation of the Garden of Eden and was in the show "Galactic Pulses" in New York. That whole show was this idea of elastic skin pulsating around a still life. I'd been working in a slow evolutionary mode, and what I saw that body of work being is: I had done stark white canvasses before, and so I was zooming out from that white and seeing the shape of that white form. They were like bubbling clouds. I've long been interested in cosmology, and I attribute that first seed of wonder to a class I took at the San Francisco Art Institute called Cosmology and Imagination. They had brought over a physicist from Berkeley, and it was the first time I was introduced to quantum mechanics, and it just opened up my mind.