October 2016

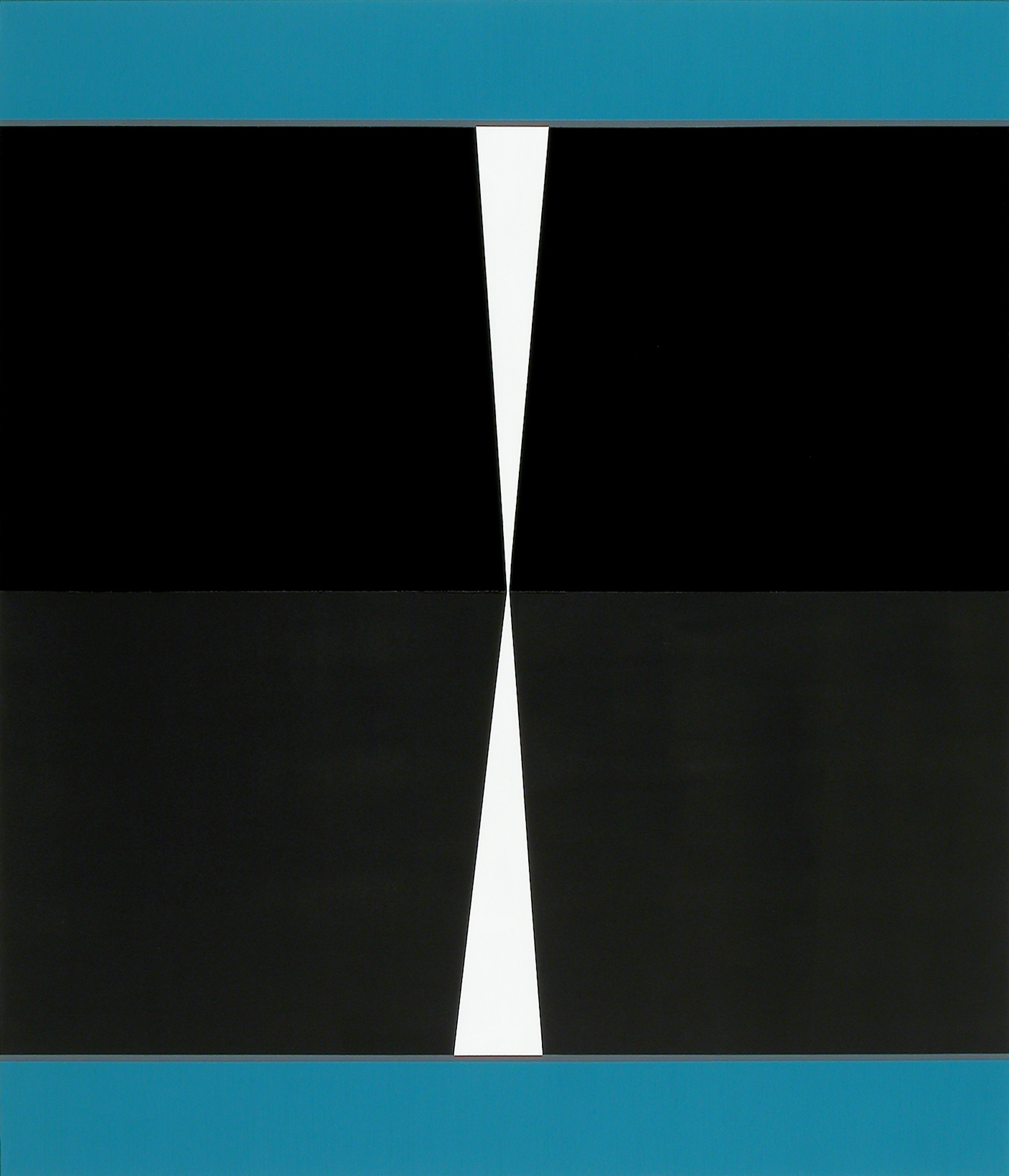

Don Voisine, “Fairlane” (2015)

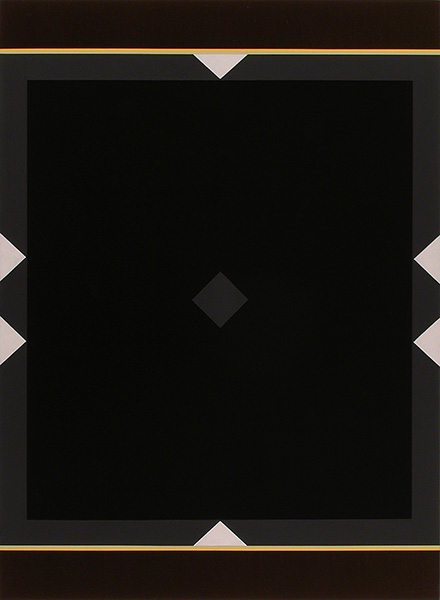

Don Voisine, “Game On” (2012)

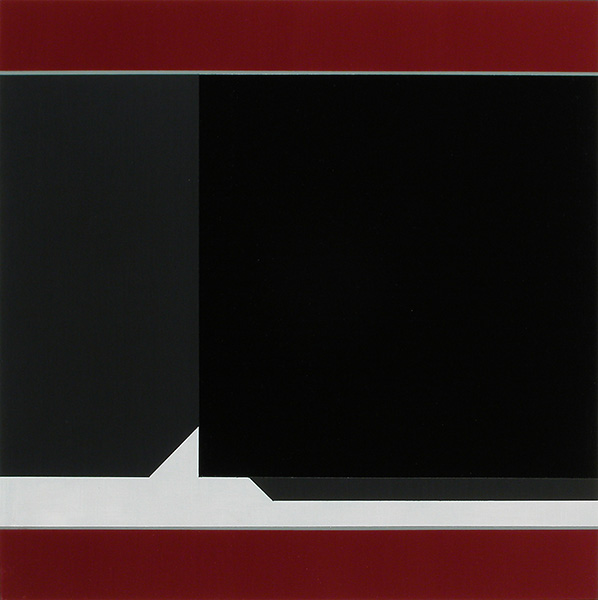

Don Voisine, “Stagedoor” (2015)

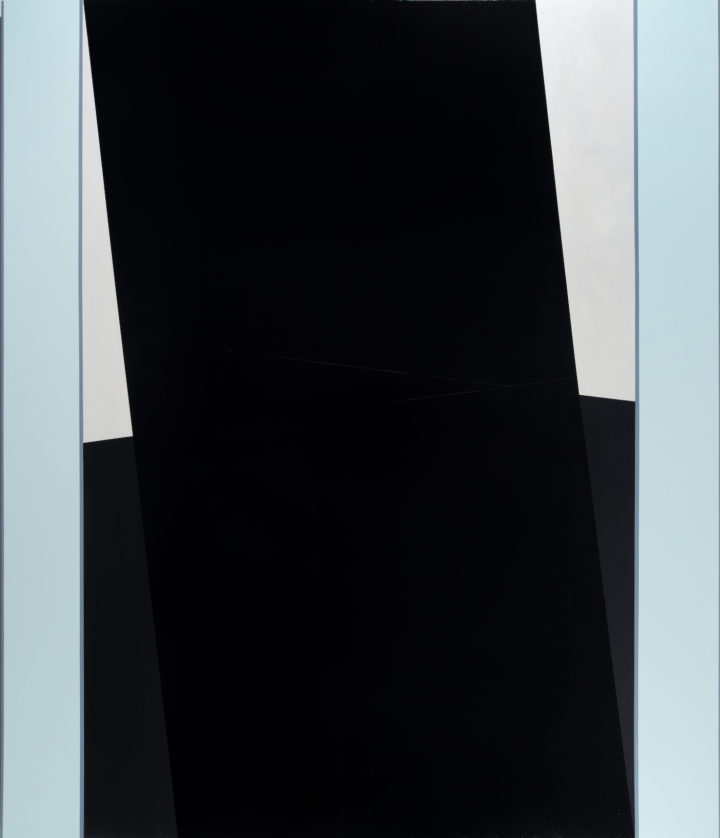

Don Voisine, “List” (2016)

Don Voisine’s Universe of Shapes

Don Voisine’s pieces demand attention; you need to study them up close and from a distance to fully appreciate the illusions the artist creates by way of a handful of shapes and a limited but resonant set of colors.

Carl Little

Back in 1987 when I was associate editor at Art in America magazine, I was asked to review a show of new work by the geometric-abstract painter Harvey Quaytman at the David McKee Gallery. I visited the exhibition to take notes. Quaytman was working with what I took to be a simple hard-edged cruciform shape. The pieces seemed repetitive, variations on a theme, and I treated them as such.

Not long after turning in my review, the magazine’s editor, Elizabeth Baker, called me into her office and explained that I had overlooked a number of details in my description of Quaytman’s paintings. She suggested I return to the show and look harder. I did so and realized my first viewing had been superficial, that there was a great deal more going on in the canvases — in their surfaces, design, palette — than I realized. It was an excellent lesson in looking at, and documenting, the work of a nuanced abstract artist.

Each of the 27 oil-on-wood-panel paintings in Don Voisine: X/V, a 15-year (2001-2016) survey of the Maine-born, Brooklyn-based painter currently on view at the Center for Contemporary Maine Art, presents a seemingly uncomplicated format, often consisting of broad, black, hard-edged central forms, sometimes X-shaped, sometimes diagonals, with triangular notches of different sizes along the edge and stripes and bands of color at top and bottom or on the sides. As with Quaytman’s work, there is more to these constructed compositions than meets the eye.

Voisine’s pieces demand attention; you need to study them up close and from a distance to fully appreciate the illusions the artist creates by way of a handful of shapes and a limited but resonant set of colors. Several paintings, for example, feature subtle tilts in the black shapes that conjure doorways or windows. Others play on surface shifts such as dividing a shape into matte and glossy sections or by way of subtle overlays.

There is a good deal of variety in the scale of the work in the show. Some of the pieces are near monumental — one could imagine some of them being translated into sculpture — while two cases in the middle of the gallery contain several miniatures. The formats also change as one circles the gallery. Along with square and rectangular pieces, Voisine offers narrower horizontal and vertical compositions as well as diptychs where the pieces mirror each other. To look over a wall of his designs from across the room is to witness a kind of abstract Morse code.

Within his universe of shapes, Voisine will often play with expectations. “Reset,” 2015, follows the pattern of echoing shapes — large black Xs and triangular notches — but the two small triangles in the center of the rectangular piece don’t line up, a slight change that nonetheless throws off the symmetry one has come to expect.

“Game On,” 2012, is aptly named. The 30-by-22-inch painting might be a design for a constructivist pool table featuring six triangular pockets and a central diamond-shaped bumper. In some ways, Voisine’s approach to abstraction calls to mind game theory. What moves will the artist make in his next painting to engage his audience?

Voisine will frequently latch onto a theme and paint variations on it. “Stagedoor (Matinee)” and “Stagedoor,” both 2015, divide the square (18 by 18 inch) panel into two main sections: a curtain shape to the right taking up two thirds of the space and a door shape in the remaining third to the left. In “Stagedoor (Matinee),” the latter shape is white, evoking the experience of coming out of a dark theater into daylight. These paintings represent constructivism as a kind of theater.

A dark humor emanates from a couple of pieces. One might excuse smirking upon spying the title “Robespierre” next to a large (60 by 32 inch) vertical painting from 2016 with a guillotine shape embedded in it. His paintings often conjure such associations. As John Yau observed in a review of Voisine’s work at McKenzie in 2013, “All kinds of feelings and possible readings come into play.” He adds, “This is one of the deep, abiding strengths of the artist’s best paintings; they become analogical.”

Another example of this: “Fairlane,” 2015, features bands of blue at top and bottom that might have been influenced by the color of one of those classic 1950s-1960s car. What is more, the center section of the painting brings to mind a highway, with the narrow attenuated white triangles that separate two dark halves evoking Joni Mitchell’s “white lines on the freeway.”

In that same review, Yau noted how Voisine’s compositions at times extend horizontally to become panoramic in feeling. “Mesa,” 2013, exemplifies this sense of the landscape: its arrangement of shapes represents a hard-edge rendering of a southwestern tableland.

Where Voisine’s earlier work often referenced specific architecture, including the floor plans of places where he lived and worked, the paintings here are more universal and iconic, achieving a kind of purity that can stop you in your tracks. Such is the experience with the large-scale “List,” 2016, which hangs near the entrance to the show. The central towering shape, leaning to the left, has a presence akin to the monolith in “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

It might seem curious to talk about motion in these solid works, but dynamic they are. The bands and stripes of color play a role in this, activating the visual field, while the interacting shapes create the illusion of movement. Critic Carol Diehl once stated that Voisine’s paintings could “give new meaning to the term ‘passive aggressive.’”

CMCA Director Suzette McAvoy has noted that she chose Voisine for the inaugural season of the center’s new building in Rockland because she felt the work was eminently suited to the contemporary space. Her impulse proves spot-on: the work feels so at home here that you can anticipate the distress of the preparators who will be taking down the show at the end of October.

CMCA has produced a handsome catalogue, with an introduction by McAvoy and an appreciation by Ken Greenleaf, an artist who works in similar territory. While beautifully reproduced, the paintings lose nearly all their nuance of gradation and shifts. I was reminded of seeing my first Rothko paintings in an art history textbook and not realizing till viewing his retrospective at the Guggenheim in 1978 how electric and resonant and gorgeous his paintings are firsthand.

With exhibitions of the Cuban-American Carmen Herrera at the Whitney Museum (through January 2, 2017) and Agnes Martin at the Guggenheim (through January 11, 2017), abstraction of the geometric variety finds itself in the critical spotlight. Voisine, now 64, makes a case in this choice sampling of his work to be considered among the outstanding purveyors of clean lines and sharp edges, the American Malevich if you will, constructing one stunning painting after another.