May 2017

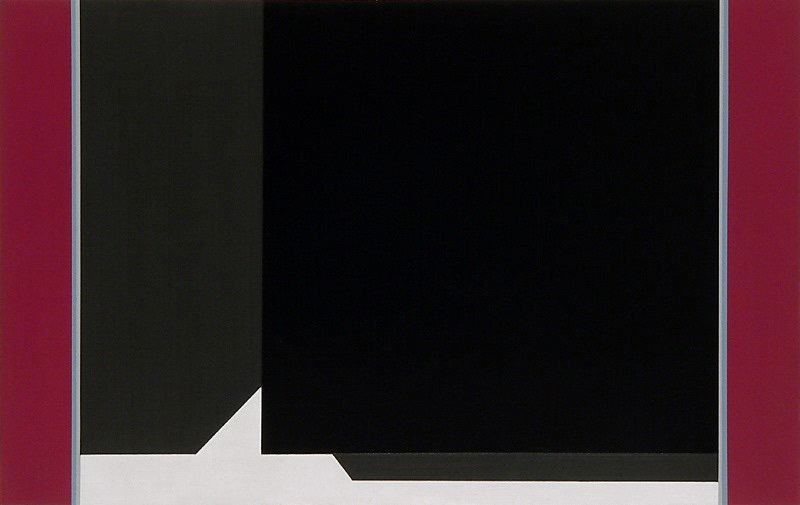

Don Voisine, “Enter” (2017), oil on wood panel, 14 x 22 inches (all images courtesy McKenzie Fine Art)

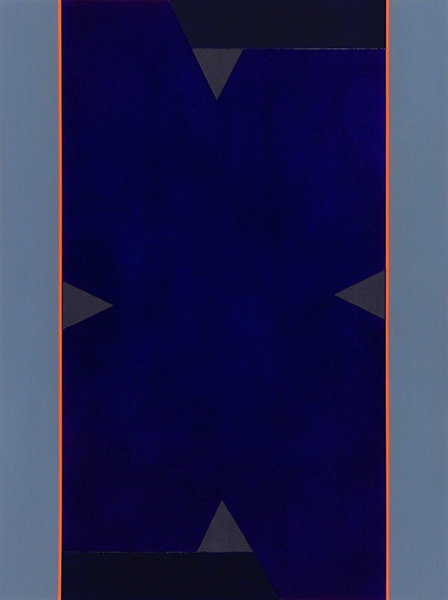

Don Voisine, “Stones River” (2017), oil on wood panel, 24 x 18 inches

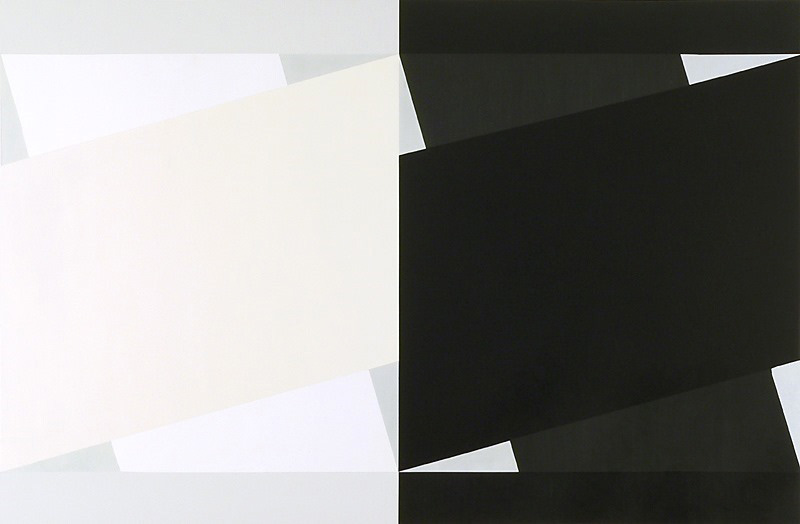

Don Voisine, “Umpire” (2017), oil on wood panel, 53 x 80 inches

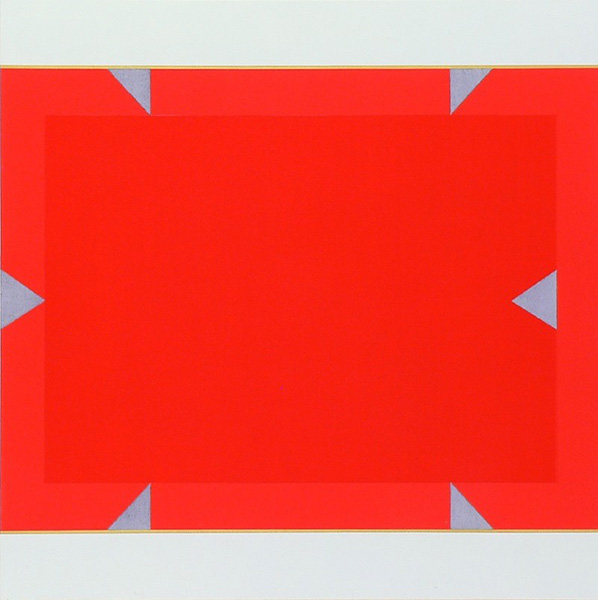

Don Voisine, “Spoke” (2017), oil on Wood, 24 x 24 inches

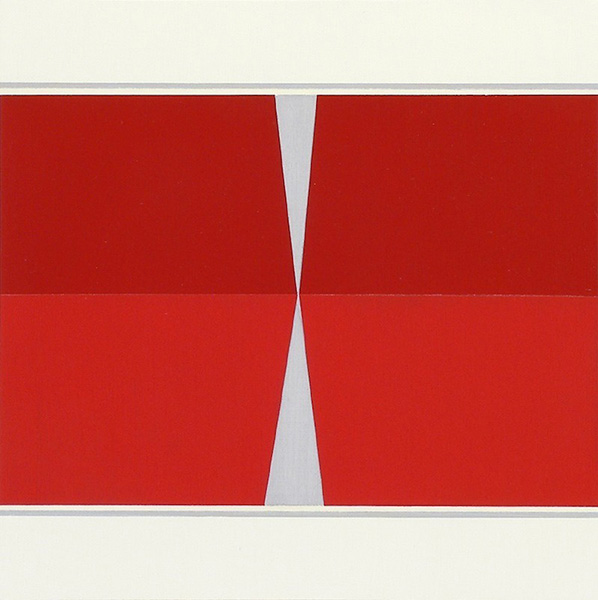

Don Voisine, “Parting” (2017), oil on wood panel, 12 x 12 inches

Don Voisine Makes Geometry Sexy

Every color in a Voisine painting has its own material identity. Even the narrow bands edging or running through the panel’s border colors convey a distinctive feel to their physicality.

There are seventeen paintings in the exhibition Don Voisine at McKenzie Fine Art (May 5 – June 18, 2017). They are done on panels, which have been cut into squares and rectangles, vertically or horizontally aligned. There is a diptych with each panel the same height but a different width. The narrow space between them adds another tension into our experience. The smallest painting measures 12 x 12 inches, while the largest is 53 x 80 inches and one of his best. Within his circumscribed vocabulary of geometric forms, Voisine never repeats himself. The shift in scale quietly underscores our need to pay attention.

The carefully sectioned surfaces contain matte and glossy shapes: clearly delineated geometric areas where the paint’s skin is palpable and the brushwork directional, or clearly delineated areas where it is thinly applied, granular and porous. Evidence of the hand is everywhere, but never emphasized. From the scale, placement, and color of the forms, to the bands that run along the top and bottom edges of the panels or press in from both sides, to the strips of unexpected colors running across the band’s interior borders, nothing is left to chance.

Every color in a Voisine painting has its own material identity. Even the narrow bands edging or running through the panel’s border colors convey a distinctive feel to their physicality. The shifts between the sectioned areas can be tonal or sharp, but the vocabulary is solidly geometric: trapezoids, parallelograms, triangles, rectangles, and squares. The angled planes add a torque to the compositions. It is as if everything is held in a state of suspension, with the actions of falling, slipping, and sliding implied.

As I wrote in a review of his last show at McKenzie, his geometry is one that is under constant pressure, where gravity becomes a felt presence on the diagonal alignment of the planes. The pressure runs along the seams where adjoining sections meet; it varies in strength but is never absent among the composition’s tightly wedged planes, both small and large. This is an exhibition of tensions between the spatial and the planar, color contrasts and tonal shifts, palpable forms and hinted-at spaces, often all in the same painting.

It is as if the artist wants to quantify how much tension he can fit into a single painting, how taut can he make each composition. The contrasts can be both sharp (black against white) and nuanced (glossy black against matte black), and often take place in one relatively small area of a painting. They are like magnets within the composition; they invariably pull you closer.

Look at all the different things he has going on in “Umpire” (2017), the largest painting in the exhibition, and you will see what I am getting. It as if he has taken Josef Alber’s examination of color and dragged it through a two-color Kasimir Malevich and come up with a Don Voisine: his combination of grays, whites, and blacks in what is essentially a two-part painting is spectacular.

These are the pleasures these paintings offer the viewer who cares to think about how complicated the everyday act of looking actually is, who is able to slow down long enough to pay attention to things as real as surface, color, density, and space. The tension between the painting-as-container and the planar forms wedged, as well as layered, into it, is exquisitely tuned. I am reminded of a cinematographer’s attention to dramatic, often erotic moments occurring within closely focused areas: the slip of air hovering between lips that are about to meet, or having just parted. The two different shades of deep red in “Parting” (2017), along with its glossy surfaces and carefully applied coats of paint, and the tips of the bisected pentagons about to meet, brought such a cinematic scene immediately to mind.

In a Voisine painting, everything is developed to a firm yet delicate pitch. Despite the modest scale of many of the paintings, the forms within them feel monumental. For no rational reason, I was reminded of Ronnie Bladen and Tony Smith, perhaps because their geometric forms were emotive. It is not the first time these artists have come to mind. They were maverick sculptors who transformed geometry into a vehicle for their imagination. Like them, Voisine does not shy away from the imagistic in his work. Like them, his painting leads to unexpected places and conjures wild associations.

In “Spoke” (2017), Voisine uses two glossy, flamboyant reds. The six pale gray-blue triangles pointing inward from the painting’s four sides grip a smaller red rectangle within a larger red plane in a different shade. Nothing ever settles down between these two very red reds. The optical vibrancy is delicious and unsettling. In this work and others in this wonderful exhibition, Voisine’s painting attains something far greater than its parts, something that captivated this viewer’s attention.

Since 1999, when he first introduced a diagonal form in his work, Voisine has incrementally magnified the pressure, even as he used increasingly unlikely color combinations, as in “Spoke.” We often talk about artists or writers being at the top of their game, and doing the best work of their career. In Voisine’s case, this is not an exaggeration, but a fact. Within the circumscribed, geometric domain he set out to explore, he is slowly but confidently pulling out all the stops without letting go of the geometry that got him where he is. He took the forms and kept doing something to them. Nothing about him or his work is settled. He has not become predictable. That is an achievement to be reckoned with.