September 2018

Demotic Abstraction with a Twist

By concentrating on detail, which is a central feature of Barbara Takenaga’s work, she has gone against the reductive tendencies of Minimalism that still haunt painting.

Since the beginning of this century, painter Barbara Takenaga has slowly expanded her project, moving from a set structure, which she explored, to an open-ended process in which meticulous control and the surrender of power interact with one another, with unexpected results. While she was doing this, she was also expanding her vocabulary to include Japanese symbols, such as a pattern of fish-scale lines, into her work. Another image resembles a geyser of steam rising into the air, its base framed by concentric rings punctuated by dots.

By concentrating on detail, which is a central feature of Takenaga’s work, she has gone against the reductive tendencies of Minimalism that still haunt painting. In her earlier work, she incorporated her details within all-over compositions, making them part of a larger, highly orchestrated field. Over the past few years, and particularly in her current exhibition, Barbara Takenaga: Outset, at DC Moore Gallery, the artist has moved into a fresh territory. She has transformed the roots of her work (graphic art and the Pattern and Decoration movement) into something in which repetition has broken free.

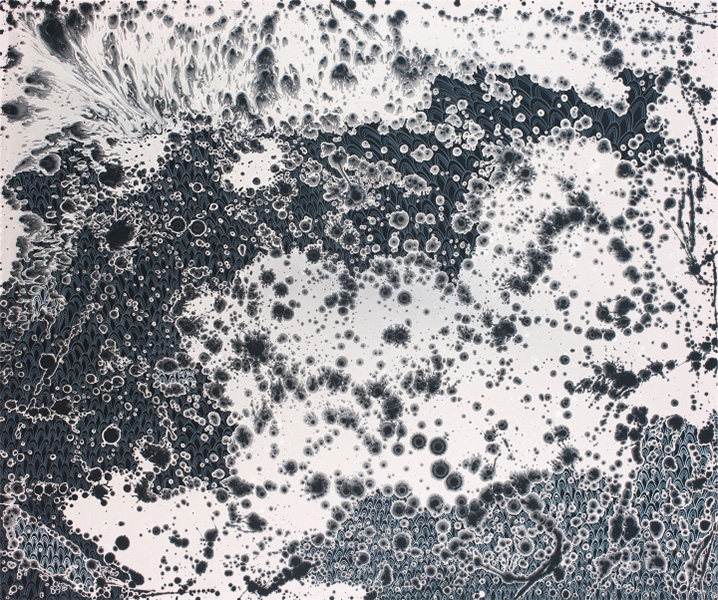

This means that Takenaga has become more focused on composition. Her recurring subject is a view of nature that is simultaneously real and imagined. In “Serrulata” (2018), the artist layers multiple vocabularies and processes — patterns, pours, splotches, and drips — without trying to order them into an all-over composition. The palette is composed of contrasts — dark blues, blacks and grays — that further compress the layered space, in which different kinds of marks are pressed together. Instead of being soothed by repetition, we are given disruption. “Serrulata,” the painting’s title, is another name for the Japanese cherry tree, which is central to the spring cherry blossom festival. The pink flowers blossom for about two weeks before falling; the transience of their beauty is reminder of the life’s brevity.

By working with blacks and dark blues, Takenaga resists the inherent beauty of the festival’s colors. The different vocabularies that she brings together — a repeated arch and the drop of black paint spreading on the painting’s surface — evoke order, repetition, dispersal and decay. The lack of a determining, overall pattern enhances our experience of looking at the painting; we get lost in it, perhaps scrutinizing only a small part. We will likely enter into the painting differently the next time we look closely. The black drops that are spread unevenly across the surface also suggest, to me, the vulnerability of art — that it, too, is subject to nature. I was reminded of the beauty one finds in damaged works.

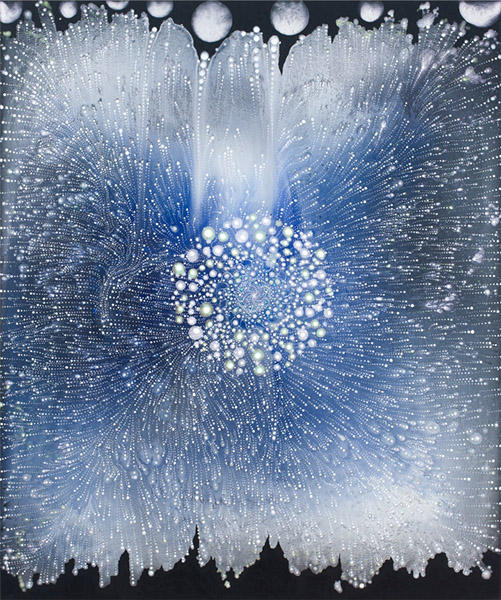

In other paintings, such as “The Edge” (2018), she evokes meteor showers. What gives Takenaga’s work a deeper resonance than one encounters in much contemporary abstraction is her allusion to of a world under constant pressure and in a state of relentless change. What also strikes me is the work’s overt visual appeal. A field full of beaded lines going in multiple directions simultaneously is visually sensual. Meticulousness and pleasure meet in these marks. It is clear the artist is attentive to each shift in direction, as none of the rhythmic lines repeat themselves. The dance between order and individuation is precise and exquisite. Looking at the vastness of space that “The Edge” embraces conveys the possibility of solace in this time of terror and disruption.

“Manifold 5” (2018) is a five-panel painting that seems inspired by Japanese screens. In her catalog essay for this exhibition, Lily Wei states: “Some of the shapes in these paintings are silhouetted abstractions of imagery taken from byobu (Japanese folding screens) and traditional Asian paintings.”

The palette is largely black and silver. What Takenaga has absorbed and transformed into her own is the combination of austerity and lustrousness that one finds in Japanese screens. In “Manifold 5,” a black curved (or phallic) shape occupies the central three panels, framed by a silvery phallic shape entering in from the painting’s right side and a silvery, largely monochromatic panel on the far left. There are numerous geysers spread across the black and silver shapes, suggesting another world that exists beneath the surface. A web of blues lines that shifts from fish scale to grid also demarcates the black shape. In places the silver surface seems to be in a state of decay. Again, what Takenaga is able to do is use the details of a painting — be it a painterly incident or an image — to inflect the entire composition, add a different note of feeling.

By moving from an emphasis on all-over compositions, guided by repetition, to a focus on the possibilities inherent in the details, and by bringing together her penchant for scrupulous devotion and her acceptance of chance, Takenaga has pushed her work into a territory all her own. In this show — which ranges from large, multi-panel works to ones you can hold in your hand — what impressed me most were the different vocabularies she had gathered together, from images and patterns inspired by Japanese art to natural forms seen under a microscope to tight patterns derived from fractals. Images and processes derived from biology, mathematics, and astronomy mixed with classical Japanese art and mid-century abstraction add up to a heady mixture. What offsets it all is Takenaga’s refusal to become hermetic or esoteric: you feel a democratic impulse running through all her work, a commitment to the possibilities of a high-minded visual pleasure that anyone can enjoy.