July 9, 2016

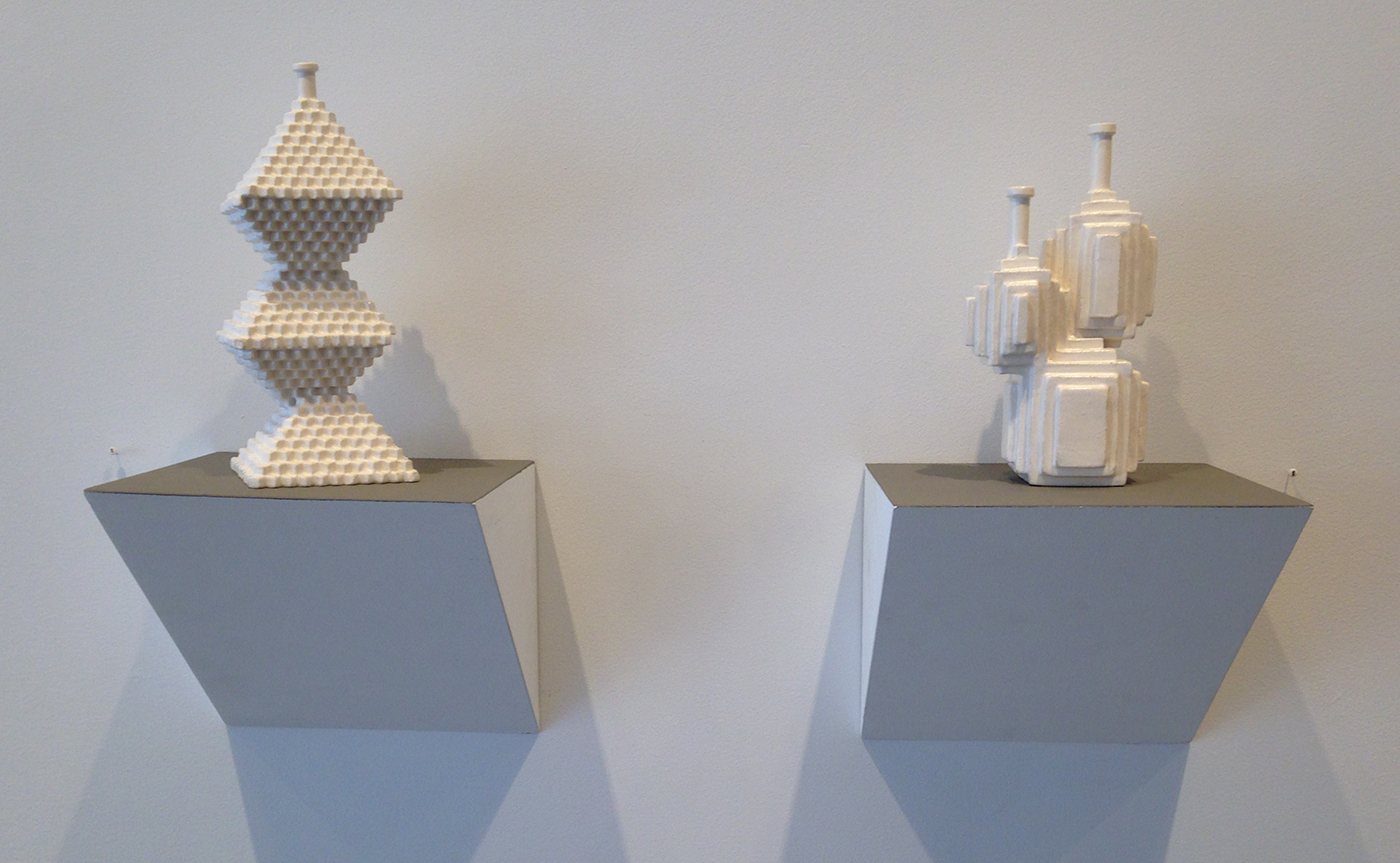

Will Yackulic, “Module 3.2” (2014), glazed earthenware, 9 1/4 x 4 x 4 inches; “Module 2.2” (2014), glazed earthenware, 7 1/2 x 4 1/4 x 3 1/2 inches (click to enlarge)

Don Voisine, “Revolver” (2016), oil on wood panel, 44 x 44 inches

Painting from the Ground Up

Thomas Micchelli

The first paintings you see in Construction Site, the new exhibition at McKenzie Fine Art on the Lower East Side, are three slabs of red polyurethane resin with wood inlays by Noah Loesberg. Collectively titled “Illuminated Manuscript Page” (all 2016) and numbered 14 through 16, they seduce you in a second, opening the show with a quiet sensuality that belies the headiness so often associated with geometric art.

This subversion of expectations goes for much of the work in the show. The exhibition’s title, as explained in the press release, invokes “the influence of architecture and the built world on abstraction,” but that aside, what the show offers above all is a lot of really fine painting.

Loesberg’s work in particular strikes the theme on a lyrically metaphorical note. His “Illuminated Manuscript Pages” (again from the press release) “reference architecture depicted in Islamic manuscript painting,” and they do so with a high degree of polish and invention. One of the pleasures of looking at these pieces is to contemplate the intuitive leap it took to turn the two-dimensional images of the source material into meticulously crafted objects in wood; whether they are meant to represent plans, sections, or details is left up to the imagination.

The inlays, composed entirely of joined right angles, can be interpreted as empty rooms or blood-red pools, spatial illusions or flat abstractions, ancient habitats or orbiting spacecraft. The resin, which laps and bubbles at the edges of the wooden slats, forms a waxy, translucent body that embeds the design like the copper circuit of a computer chip — an inversion of the natural and the artificial, with the wood impersonating metal and the polyurethane reading as cyborg flesh.

Other inversions take place in Samantha Bittman’s two works, both untitled paintings from 2016 in acrylic on hand-woven textiles. These geometric patterns, which border on optical art, are composed primarily of black-and-white or orange-and-white strands, while the painted overlays continue the patterns in reverse coloration (white to black, black to white; orange to white, white to orange). They are reversals hiding in plain sight, slippery disjunctions between artifice and reality.

Altoon Sultan can be seen as pushing Bittman’s inversions further with two examples of her multifarious practice: an egg tempera (“White Wall,” 2015) done in Neo-Precisionist style, with a frontal composition, shallow Cubist space, and realistically rendered light and shadow, and a geometric abstraction (“Blue Squares,” 2016) made of hand-dyed wool hooked on a linen backing.

Liv Mette Larsen also works in egg tempera, and in a manner that could also be considered Neo-Precisionist, but in a more abstract vein. Working from observation, she strips away details to leave nothing but planar shapes floating on monochromatic fields. It’s an affectless approach that evokes an Outsider-ish ingenuousness through unfussy brushwork and flat, earthy color.

The four oil paintings by Cathryn Arcomano, an artist who died in 2012 at the age of 88, are small (8 x 8 inches) and make use of gold and silver grounds. Dating between 2006 and 2008, each is composed of two elements, a rectangle and a circle, which overlap in the center of the canvas. The imagery is based on architectural motifs found in paintings by Fra Angelico, whose frescos in the Convent of San Marco in Florence prominently feature columns and arches, mirroring the building for which they were made.

Fittingly, Arcomano’s works are hanging beside two abstractions by Alison Hall, both made this year, based on the star-studded ceiling frescoes and floor mosaics of Giotto’s Arena Chapel. Done in oil and graphite on a Venetian plaster ground, these dark, mesmerizing paintings are objects as much as they are images, with a density of pigment that is simultaneously weighty and vaporous. The reflective graphite patterns covering the matte surfaces, almost invisible on first glance, glint like bits of flint across a nocturnal expanse, adding the physicality of light to the otherwise light-absorbing fields (one in indigo and the other in black).

If the paintings of Hall, Arcomano, and Loesberg offer oblique allusions to ancient art and architecture — a set of hidden agendas, as it were, none of which impinge on the works as standalone statements — the quirky ceramic sculptures of Will Yackulic literally hide objects inside their cavities, which are permanently sealed by the firing process behind white-glazed earthenware walls.

Titled “Module 2.2” and “Module 3.2” (both 2014), the sculptures are made up of three faceted geometric forms (rectangles for “2.2” and diamond shapes for “3.2”) with small cylindrical smokestacks on top, as if they were curiously designed miniature stoves or scale models of fantastical factories. The concealed objects are personal items from friends of the artist, making the vessels into secular reliquaries, a gesture that feels pointedly, even radically private within a social media landscape where conditions for membership seem to require baring it all.

Yackulic’s pieces are the only explicitly sculptural objects in the show, but Christian Maychack’s “Compound Flat #46” (2015) lies somewhere between a polychrome relief and a deconstructed painting, with colorful, irregularly shaped swathes of epoxy clay attached to laminated slats of wood. Close by, Erin O’Keefe displays sculptures-after-the-fact — color photographs of a studio setup composed of a mirror and narrow lengths of wood configured into eye-teasing geometric combinations of plane, line, and reflection.

Jason Karolak continues his explorations of linear, florescent paint strokes on a black field, but he has dispensed with his usual freewheeling approach for something more deliberate: three out of the four easel-sized untitled paintings presented here (all 2016) are quasi-symmetrical wireframe designs involving rectangles, triangles, and parallelograms that flip back and forth in space, or lie flat against the picture plane, depending on how you choose to look at them.

In the fourth painting, “Untitled (P-1623),” a dozen light blue horizontal and vertical bars float above a pool of deep violet framed by a black border, which is brightened by an interior edge in light blue and green. Tiny blue squares, like blinking lights, appear in each of the panel’s four corners. Looking at the image has a hypnotic effect not unlike gazing into a computer screen, with its luminescence and depth. There are no direct nods to technology, simply the manipulation of electric color.

Don Voisine has made a virtue of sticking to a highly circumscribed set of formal elements: oil paint on a wood panel; matte and glossy surfaces; identically colored bands across the top and bottom; and a configuration of black planes in the center. The two paintings here, “Facade” and “Revolver” (both 2016), demonstrate the nuance and experimentation possible within the artist’s chosen method.

In “Facade,” the bands are yellow and the black planes seem to recede in space, one overlapping the other like theatrical curtains drawn across a stage. A backward-tilting, notched gray plane is laid under the black shapes, augmenting the sense of space. Between the yellow band and gray plane on the bottom, and the yellow band and black planes at the top, there is an extremely narrow stripe whose color hovers somewhere between pink and peach, a dash of sweetness that tempers the austerity of the design and signals that Voisine’s geometry is not as strictly Apollonian as you supposed it might be.

Nor is it Greenbergian, despite the resolute flatness of much of his work, as evidenced by the spatial shift in “Façade,” a surface disjunction that is pushed even further in “Revolver.” Colored in classic Bauhaus red, white, and black, with a white field beneath the black planes and red bands at the top and bottom, the painting takes its name from the beguiling arrangement of the black shapes in the center.

A narrow vertical axis in matte black bisects a glossy black rectangle whose sides are parallel to the physical edges of the wood panel. Shim-like triangles in matte black appear on all four sides of the glossy rectangle, suggesting a tilted plane of equal dimensions right behind it. This simple addition to the otherwise decidedly rectangular composition seems to set both planes — the visible and the implied — spinning like a revolving door. It’s a flagrant violation of painting’s essential flatness, a disorienting and funny take on what a straightforward collection of geometric shapes can do.

The exhibition — which also includes a colorful jigsaw composition by Mel Bernstine; two muted, planar paintings by Eric Brown; Kellyann Burns’s starkly vertical evocation of a cityscape; a diamond-patterned acrylic on canvas by Paul Corio; Gary Stephan’s abstraction superimposing a Swiss cross over a large X-shape; and Laura Watt’s spiraling, expressly architectural composition suggesting the interior of a dome — doesn’t lean too heavily on its premise, avoiding the literal in favor of a more allusive approach.

Construction Site is a reminder that Modernism was founded on Cezanne’s reduction of nature to the cylinder, sphere, and cone. In painting, as in architecture, formal innovation lies in the organization of space, and if you plan to reinvent painting from the ground up, these are the building blocks, along with Mondrian’s grid and Albers’s square, you’re going to use.