Neo Geo Trio

Fresh patterns emerge from SF's post-Mission School landscape

BY JOHNNY RAY HUSTON

Wednesday April 9, 2008

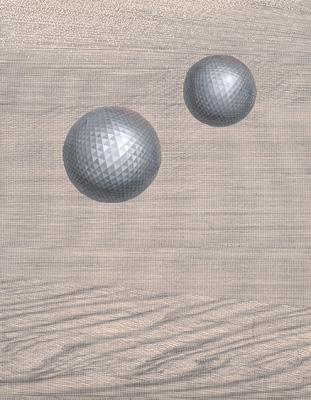

Will Yackulic's Some Time to Mend the Mind

"Bay Area Now" roundups have come and gone since Glen Helfand coined the term "the Mission School" in an influential 2002 Guardian cover piece (See "The Mission school," 04/07/02). Exactly six years later, the "heartfelt, handmade" traits Helfand described still hang heavy over or range freely through local art aesthetics, even if a few core creative forces from the loose movement - Alicia McCarthy, especially - didn't cash in on the cachet of a higher profile. But April is always a month for growth: this year it brings a trio of shows by San Francisco (or SF-to-NYC) artists who've moved through or around Mission School color and figuration, forging a new direction and forming a new pattern.

Call it 21st-century Neo Geo, though the tag might not apply to what these artists will be doing 12 months from today.

A playful approach to geometric shape is at the core of distinct traits shared by Todd Bura's, Ruth Laskey's, and Will Yackulic's new shows. Dozens of triangles form formidable spheres in "A Prompt & Perfect Cure," Yackulic's collection of 10 works on paper at Gregory Lind Gallery. These spheres have been likened to geodesic domes, disco globes, and IBM Selectric typewriter balls. I'd throw in mentions of Asteroids and the orb from Phantasm (1979) for good measure, though such 1980s pop cult references are no longer as near the forefront of Yackulic's visuals as when he offered a twist on the phrase cubist via images that suggested the video game Q-Bert gone existentially lonely. Yackulic's new work is a breakthrough, due to sheer inventiveness: in all the show's pieces, he paints with a typewriter.

Throughout most of "A Prompt & Perfect Cure," Yackulic uses endlessly repeated asterisk and period symbols to generate waves and horizons of visual energy, and sometimes even employs the typewriter to create the show's signature orbs. Like op art, the resulting pieces lure one to press one's face against the object itself, and they take on three-dimensionality when viewed as group formations from a distance. The potent, disconcerting humor of Yackulic's show stems partly from his laconic use of text, a strategy that - along with his use of pre-electric typewriters - obliquely acknowledges his New York School poetic roots. But it stems primarily from his spheres, a gang of faceless main characters. Some are darker, some lighter, as if the viewer facing them is giving off varying degrees of glare. Yackulic also has a droll flair for timing, saving his bravuragesture for the tenth, last, and largest piece, where one orb joins another - a cause for celebration, or worry?

Some Time to Mend the Mind, the title of that duel-sphere finale, might apply in reverse to Todd Bura's "Misfits" at Triple Base Gallery. Like Yackulic, Bura has an interest in geometrically-based architectural representations of mental states. But his penchant for arranging wooden right angles results in three-dimensional sculptural forms in addition to two-dimensional painterly ones. He also has a poetic sensibility, though his gambit of giving 14 pieces the title Untitled, followed by a small group of capital letters in parentheses, is cumulatively closer to language poetry, albeit language poetry overcome with angst.

"Misfits" has a unique quality, as if Bura found fragments from his inner world, brought them to a room, then mounted or arranged them for people to see. (Its quietude and careful use of placement, akin to that of the Bay Area's Bill Jenkins, also draws attention to the space around Bura's works - even or especially if they are framed or on canvas.) While Bura might be devoted to the idea of a unfinished whole that is nonetheless greater than the sum of its parts, there are a few standout enigmas. Untitled (NIT) builds from his past explorations of - and emphasis on - paper's materiality, while remaining a riddle: does it utilize the inset of a book's cover, or is it a collage in which comics peak from the very edges of aging blank pages? (A small formation of pinpricks on the surface characterizes Bura's varied minimalism.) Perhaps indebted to Richard Tuttle, the much larger oil painting Untitled (ETRI) layers light over darkness. (Or does it cover darkness with light? Regardless, Bura plays the recurrent binary both ways.) The latter suggests a buried cross or intersection.

Ruth Laskey's approach to geometric form is based upon intersections, though her presentation, at least at first glance, trades Bura's evocative, open-ended symbolism for a plain approach that recognizes that literal meaning is many-faceted. As the saying goes, Laskey's "7 Weavings," at Ratio 3, is what it is: seven tapestries from her ongoing "Twill" series, where the structures or perhaps strictures of the loom and the diagonals of twill shape help form diamonds, triangles, pyramids, and crosses of color. Like Yackulic, Laskey's process involves extreme repetition that yields varying waves of visual energy - albeit megaminimal, muted waves that might require squinting. As Rachel Churner notes in a recent Artforum essay, Laskey's tapestries "are not fields for projection, but rather instances of the figure being imbedded in the ground itself."

One of the rich literal pleasures of Laskey's tapestries is their deployment of specific reds, blues, yellows, and greens, which is less antic but just as imaginative as the peak Mission School-era in terms of drawing from Josef Albers's color theories. At times, new hues emerge from the intersection of two individual colors that Laskey has first created by blending dyes and then painting the thread that she weaves through cloth. There's an inscrutable quality to "7 Weavings" that echoes that of Bura's and Yackulic's shows: the colorful cloth shapes Laskey forms might as well be flags for countries in a world a bit more observant, and less brutish, than our own.