October 21, 2016

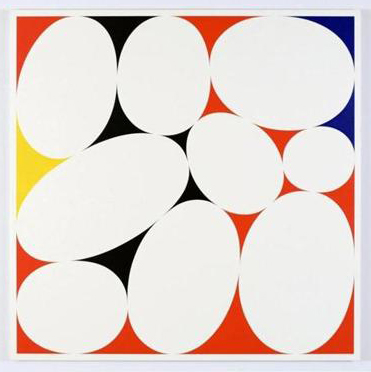

Cary Smith, “Ovals #31 (red-black-blue-yellow),” 2015. Courtesy of the artist, and Fredericks & Freiser, New York.

At deCordova Museum, a strong New England Biennial

“The one thing I have in common with any adult I meet is childhood.”

That lovely quote is from Ashley Bryan. In 1962, Bryan, who is now 93, became the first African American to publish a children’s book as both author and illustrator.

Prior to World War II, he was the only African American to have received a scholarship to study art at Cooper Union in New York (unlike other colleges, which rejected him, Cooper Union administered its test blind). When he served in the army during the war, he used to keep a sketch pad in his gas mask.

Bryan’s bright, ecstatic illustrations — collages and prints pulsing with fruits, lush foliage and radiant skies — and a selection of the marvelous mixed-media puppets he has been making for more than half a century are displayed in a joyous room at the center of this year’s deCordova New England Biennial.

The show, organized by departing chief curator Jennifer Gross and associate curator Sarah Montross, has no overriding theme. It simply aims to present the best art being made in the region today. It features work by 16 artists from all six New England states.

And it’s a strong show. Gross and Montross personally toured about 60 artists’ studios in three states each. Bryan’s inclusion leaps out not only because of his work — when did you last see a children’s book illustrator in a contemporary art biennial? — but because of his age. Biennials and nonagenarians don’t typically go together.

But Bryan is not, in fact, the only long-lived artist in the show. Lois Dodd is 89. She, too, attended Cooper Union and now lives, like Bryan, in Maine. She is represented here by 12 paintings of varying dimensions arranged artfully on a wall, and a selection of small painted sketches in a nearby display case.

Both ensembles reward close looking. Dodd has a transparent, unaffected style, a penchant for selecting surprising fragments from near-at-hand life, and a sense of color that’s equivalent to a muted jazz trumpet: piercing but mellow.

Two of the paintings show trees: One is flowering, the other bare. Two show skies quilted with puffs of cloud: one is a night sky, the other day. And two more show windows.

The bigger of these is “Shed Window.” Its initially unprepossessing palette of khaki green, mauve, and black gives off mysterious pulsations as you walk around the gallery. It draws your eye back.

In aesthetic terms, Dodd’s paintings are rivaled only by Cary Smith’s taut, seraphic abstractions in flat, unmodulated colors. “Stripes #3 (with 4 color border)” is a square-shaped canvas covered in three vertical stripes: light blue, yellow, and green. Thin borders of royal blue, red, orange, and black interact with these three broad stripes in ways that would be tedious to try to unpack. The sensation is not meant for analysis. It’s simply bewitching.

Smith’s other paintings are also terrific: they’re mostly organic shapes against flat grounds that create drama from the tension between the outlines of forms and the edges of the canvas, and between figure and ground.

If the works mentioned so far call out to the heart primarily through the eye, other pieces ensnare different parts of the brain. I was especially fascinated by the architectural and sculptural models of Tobias Putrih and Fritz Horstman.

Putrih lives in Cambridge, but he was born in Slovenia and in fact represented Slovenia at the 52nd Venice Biennale. His models, or maquettes, arranged in a display case, are inspired by the modular thinking of certain visionaries of 20th-century architecture and design — especially Buckminster Fuller. Made from cardboard and Styrofoam, they seem to be either in the process of falling apart or not yet completely assembled.

Out in the sculpture park, this ambiguity is deepened by his interactive pieces, which consist of two pallets piled with bricks — one red, the other gray. Viewers are invited to take one brick from the red pile and place it anywhere on the gray pile and vice versa. It’s an elegant experiment that highlights a dynamic between order and disorder that is more complex than you may think.

Horstman, meanwhile, has a series of small-scale architectural models displayed on the wall. He calls them “formworks,” and they’re his attempt to transpose the forms and often transient processes of nature — gusts of wind, eddying water, meandering creeks, tall trees — into very linear, three-dimensional “drawings.” The results are wonderfully various.

One — “Formwork for a Spiral Movement” — has been blown up to full scale and installed in the park. The materials are deliberately plain, but the experience of being inside and around the open structure is intriguing.

In the second of the two large galleries given over to this year’s biennial, I was drawn to the riveting large-scale photo-collages of Providence-based Theresa Ganz — especially “Panorama.”

A nearby series of paintings by Craig Stockwell are full of sophisticated layerings of form, but they’re marred by unhappy colors. And a video documenting an avant-garde dance performance by Kelly Nipper was visually and aurally absorbing but, in its dense thicket of references, too abstruse to connect with an unprepped viewer like me.

There are many other good things, including video installations by Academy Records and Youjin Moon exploring sonic and visual textures, and a series of beautiful photographic portraits, by Tanja Hollander, which appear simple but linger, enticingly unresolved, in the mind’s eye.

I was impressed, too, by the text-based works of Susan Howe, the flamboyant wall sculpture of Timothy Horn, the multi-media wall pieces of Heather Leigh McPherson, the hand-painted maps, magazines, and books by Carly Glovinski, and the politically charged paintings of Jason Noushin.

This is a rewarding show, well worth seeing. What’s more, this is one of the nicest times of the year to visit the deCordova. So go. You won’t regret it.