December 10, 2015

Installation view of ‘Cary Smith,’ 2015,

at Fredericks & Freiser, New York.

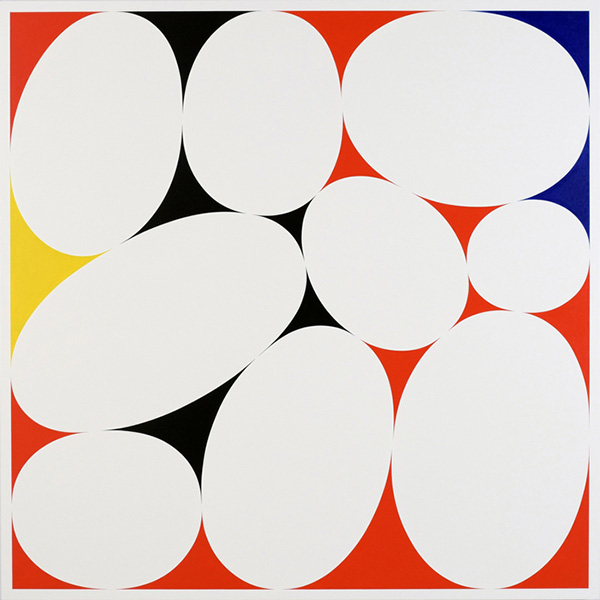

Cary Smith, Ovals #31 (red‐black‐blue‐yellow),

2015, oil on linen.

‘Perfectionism Is All Too Human’: Matthew Weinstein on Cary Smith and Jean Tinguely

By Matthew Weinstein

It’s generally accepted that improvisation signifies humanness and, conversely, that perfectionism signifies its repression. But perfectionism is all too human. Perfectionism carries with it the inevitable defeat inherent in the striving for ideals. It can be an expression of humility or of colossal ambition. Perfectionism is not a mechanical thing. It is a human thing. Perfectionism spans the full range of being.

Cary Smith makes perfectionist paintings. They are a source of pleasure to those of us who I have always referred to as “edge and corner queens.” The often multiple borders around each composition are almost perfectly aligned with the painting’s outside edge, but not so perfectly that one has to ask how the artist did it. The colors are not quite straight out of the tube, but neither do they seem too special (Smith is spared the stale appellation of “colorist”). The shapes that the colors make are familiar but not overly familiar. They don’t demand that one parse their meaning, they simply guide one toward pleasant associations. It’s an oxymoronic description, but Smith’s paintings communicate a sublime neutrality. Smith makes “types” of paintings. It often seems as though he is following a production model wherein new types are perfected and released at regular intervals. But Smith’s production departs from commercial production in that the earlier types are never abandoned; nothing becomes obsolete.

Smith’s measured control over his artistic development is a curiosity to those of us who have morphed more chaotically. In his current exhibition at Fredericks & Freiser there are paintings of intersecting straight lines, of ovals politely making room for each other, of multicolored squares lined up in neat rows on a monochrome background, of a funny splat that looks like a Matisse cutout on stick-figure legs, and of wobbly wagon wheels lined up like awkward children in a curtain call for a grade-school play.

Smith’s paintings are made out of happy sunshine. It’s a sunshine that carves the world into clearly divided shapes; it enhances colors; it simplifies and creates a lightness of spirit. The perfectionism of Ellsworth Kelly, whose work evokes expanses of cut grass and white skies, comes to mind.