September 25, 2016

Installation view, Sarah Walker: Space Machines at Pierogi Gallery, September 2016

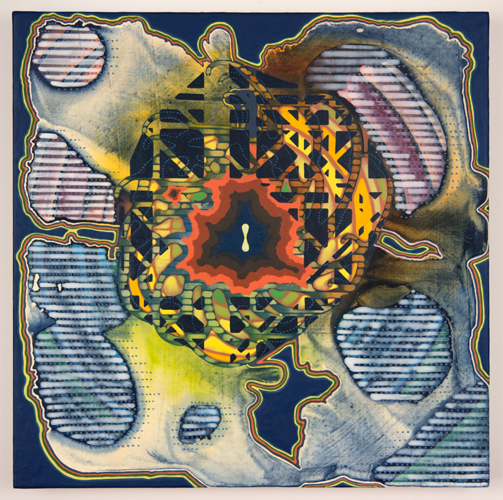

Sarah Walker, Interpoint, 2016. Acrylic on panel, 16 x 16 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Pierogi Gallery

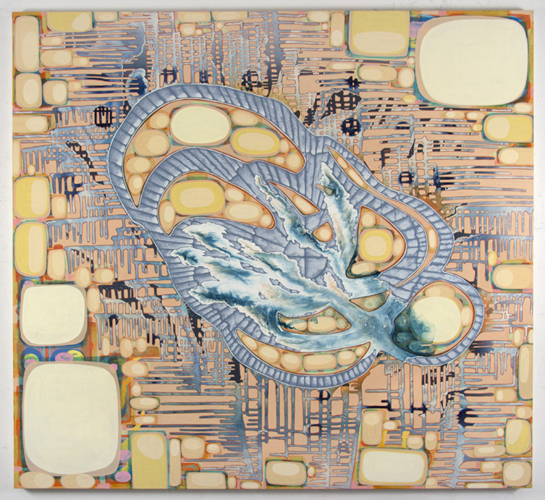

Sarah Walker, Qbit, 2016. Acrylic on linen, 66 x 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Pierogi Gallery

Sarah Walker, Space Machine I, 2016. Acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 22 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Pierogi Gallery

Sarah Walker in her studio, August 2016. Photo: Mary Jones

Brainbow: Sarah Walker in conversation with Mary Jones

by Mary Jones

Sarah Walker: Space Machines at Pierogi

September 9 to October 9, 2016

155 Suffolk Street, between Houston and Stanton streets

New York City, pierogi2000.com

For the past 20 years, Sarah Walker has been developing super complex paintings that speak to the technological imagination—webs and labyrinths of densely layered patterns and lines that hum with things we’ve never quite seen, but intuitively recognize. Networks and nerves, conduits and constellations, all mash up in a hovering, aerial perspective. Her work alludes, also, to a scientific, radiant mental space of indeterminate scale and equivocal organization, one that reverberates more brainbow than intergalactic awe.

Her multiple realities are hard-edged and clear. It is essential to her purpose that the work function at the edge of overload, dazzling and hypnotic. Her paintings have been described as orgasmic and psychedelic, and they’re only getting more so, on both counts.

“Space Machines” is Walker’s 5th solo show at Pierogi gallery, and her debut in the gallery’s new Manhattan space. In the new work, the superimposition of forms has become more pronounced, with an increased implication of motion and depth. Hot orange and yellow clusters of circuits, organs, or perhaps a cyborgian combination of both, orbit from a central spot, lifting off, or maybe levitating from the painterly ground, mapped with coagulated acrylic pools.

I met with Walker in her Brooklyn studio where she works and lives with the artist Andrew Ginzel, and their son, Walker, now 10.

MARY JONES: I want to ask about your father. He went from medicine to neuroscience and then to psychiatry and you’ve described his way of thinking as an important influence on your work. Does that account for your merging of the technological with the psychological?

SARAH WALKER: My father was in some sense the initiator of how I regard space and how I think through process in my paintings. I remember my childhood foremost as the dynamics between people, which solidified for me- a visual thinker- the reality of mental space and its “objects”. In abstraction this might be described as a grasp of embodied patterns of occurrence. I often view technological space as an extension of mental space. Space and pattern are key elements for me.

Do you feel a relationship with other artists with a similar aesthetic?

Though different from mine I feel connected to the work of Bill Komoski, Tom Burckhardt, Sharon Horvath, Glenn Goldberg and Barbara Takenaga. Each in their own way coalesces from their spaces “figures” that blink into form, but just. I respond to these as selves in the midst of multiple forces, both material and nonmaterial. It’s my way to describe to myself living in the midst of change.

There’s a greater duality in the new work, more separation between the figure and ground. Are you relating to a mind/body dialectic? I thought of Gaspar Noé’s film, “Enter The Void,” while considering your hovering compositions.

It’s a growing preoccupation, this momentary contraction of space into object, which could be described as figure and ground or self and other. Held within the architecture of the painting a multifaceted occurrence flickers into being, emerging from multiple fields yet somehow separate and unique. This may be coming about because the painting’s physical aspects adhere to psychological principles. I’m interested in gravity as attraction; the gravitational pull of one form wanting to be next to or merged with another. As this process happens, other things will get displaced, repressed, projected; they move around through the layers, alternately subsumed then revealed by way of psychological movements.

Does the “Space Machine” of the show’s title refer to anything specific?

I use outer objects to describe inner ones but I don’t think people will necessarily see literal machines. Instead, the paintings themselves offer a way to move through lots of spaces or states at the same time. I hope they work on the viewer’s psyche as visual devices.

Are these mandalas?

Yes, perhaps in how they function. I feel the title “Space Machines” is relevant here, in that my work can generate a different sensibility of existing in space, an alternate form of cosmos. I feel they can operate as useful filters for complexity. We have a simplified perceptual structure that filters out information to aid our survival. It seems, however, that the terms of survival are changing fast, and we have to be more porous and flexible in how we view the intersection of all the different kinds of material and nonmaterial realities that exists around and inside of us. What happens when all these are influencing one another in subtle and not so subtle ways is how these paintings are built, nothing goes away, it all sticks around.

Surface seems very important to you, the canvases are very considered, smooth and meticulous, a synthesis and compression of the painterly events that really show your control of the medium.

I suppose it’s a sensory thing- riding the line between seeming flawlessness and the ardent physicality of liquid pigment feels really good. The zone I’m after is where the surface seems dematerialized yet is thick with visceral activity, gritty yet flat, expanding and contracting simultaneously. That place is the seam between mind and body, technology and reality; the physicality of one’s mental space that’s shot through with feelings and textures, time and memory. That’s what I’m after.

How intuitive are they? How do you begin?

Intuition is a great tool. I begin with a totally fluid situation, pouring on a lot of very thin paint. The drying pattern is important. Sometimes I’ll flood the surface with water and drop color into it. I allow those events to flow in whatever direction the surface chooses. Once dry those chaotic liquid forms become the skeletal structure of the painting and they remain emphatically visible through all its layers.

To what degree does the process determine your images?

In the beginning to a great degree, then in the end there’s more negotiation. The paintings are formed slowly over time, arising from all that’s happened on the first liquid layer. It’s parallel to how a child grows into an adult. You don’t get to set the terms so much in the beginning, but one gets to play one’s hand more or less effectively as time goes on. The more risk, the more interesting and transformative the choices must be. The more wayward, awkward or poor those choices, the better the chance the painting will turn out vivid and come bundled with some new language. I can’t game the system, I must make my wrong turns and deal with unintended detours. It’s very important to me that I save the voice of every layer, even the disappointments, so they influence everything that comes after. Save everything, keep building.

I think of you as having a signature palette, in particular a very warm blue. Is this an intentional metaphor for space?

Yes, when I use blue it underscores space itself. Increasingly technology’s screens reinvent space to be even more blue, more cool, narcotic yet sleepless. Then I find myself using orange and other warm colors to tug in another direction. There’s an urge to make the oldest or least solid layer appear to be the last thing added- what should be sinking pulls forward and vice-versa. The painting breathes with this conundrum.

What are the rewards of complexity?

Multiplicity is what I’m after. My favorite position is where I can entertain several very different trains of thought at the same time, or be able to grasp something holistically as it’s happening. My paintings help me do that. They create a context for me to actually build the state of mind I most enjoy. That place is ambiguous, not one thing or another, maybe it is “yes, and…”.

Is science something that you follow alongside your work?

Science, also fringe science even pseudoscience. I’m intrigued by how people arrange information to create their facts. The edge of physics now is particularly fraught with ambiguity and contradiction, which makes it so fascinating. I decide to take seriously beliefs or certain worldviews if only for a period of time. I marinate in several of these narratives and the work adopts the shapes that arise from their collision or collusion.

For instance…

A recent favorite is the asteroid narrative, “Planet X”, for which I named my last Pierogi exhibition. We don’t know what Planet X is, but a lot of people think they do, and project upon it. Whole world-views have been assembled around this possibly totally fictional entity crashing into Earth or that it is an alien space craft, or our sun’s binary star on a dangerous elliptical orbit, or… So it’s an open ended scholar’s rock, a mandala, a narrative generating machine. It sparks fires in the limbic system, and can adapt itself to any association it meets. It’s always due back any day now, and ironically it was supposed to smack into our planet on my birthday, July 29th.

What was the narrative for this series?

Among other things I was reading on reincarnation. Thinking about a cyclical view of the human soul lent its language to how I approach the painting process. Alongside this I was entertaining the idea of morphic resonance, as developed by biologist Rupert Sheldrake. For him memory is stored outside of the brain in electromagnetic fields, the brain being the receiver. His idea is that you tap more specifically into that which is most related to you, and then less so the more general the connection. Preoccupying myself with these things provides me a way of moving through the painting process- it’s like choreography.

Do you think these narratives and ideas are discernible to the viewer?

No, I hope they fall away. The ideas were scaffolding. Narrative structures that play in my imagination, like color choices, guide the process. However where I cared and where I pushed away, or focused and then fell apart, what I loved and then rejected that nonetheless returned- people can feel those movements. The weave of decisions and positions is dense enough so that the painting can assemble itself for each viewer using their own unconscious diagram. Each painting is different, allowed to develop through improvisation along its own path. Each is like an egg; carrying with it the nutrients needed to sustain scrutiny. They are sturdy enough to exist anywhere and still transfix someone, anyone.