April 6, 2013

Sarah Walker, Volatile Compound, 2012. Acrylic on panel, 20 x 22 inches. Courtesy of Pierogi Gallery

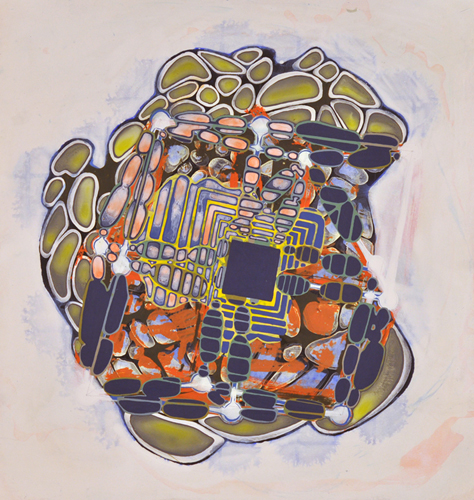

Sarah Walker, Near Earth Objects XII, 2013. Acrylic on paper, 14 x 13.25 inches. Courtesy of Pierogi Gallery

Quantum Fields and Cellular Processes: Sarah Walker at Pierogi

by Dennis Kardon

Sarah Walker: Planet X at Pierogi Gallery

March 22 to April 21, 2013

177 North 9th Street, between Bedford and Driggs avenues

Brooklyn, 718.599.2144

Sarah Walker’s art is like visual quicksand. From a distance, these pulsating, energized paintings with their alluringly complex, multi-patterned surfaces seem rationally concrete and firmly structured. But upon closer investigation, subtle incongruities quickly leave us unmoored.

Colors that appeared transparent reveal themselves to be opaque, and lines that seemed to float on the surface turn out to be artifacts from earlier layers. Metaphors mutate from the cosmic to the subatomic. A form collapses into a hole, and patterns cohere into gateways to other dimensions. Each painting is a labyrinth: trying to deconstruct how these works are made could lead to madness. Nothing is ever what it initially appeared to be. Surrendering one’s mind to Walker’s twisted relational structures is to become a mental fly caught in a sticky web of visual contradictions.

Planet X, Walker’s title for her fourth show at Pierogi, is neither about the solar system nor X-rated, although her work can feel, both cosmological and orgasmic. There are nine small acrylic paintings on reverse-beveled wood panels, and a constellation of works on paper from a series called Near Earth Objects. The paintings are abstract, but not in a conventional sense. Though they do not represent figures, still-lifes or landscapes, the language used to describe them is resolutely pictorial. Allusions to quantum fields and cellular processes spring inescapably to mind, even though no actual scientific principles are illustrated.

Volatile Compound (2012) – a painting that is easy to overlook, exiled over Pierogi’s flat files in the gallery’s outer vestibule – is a vital bridge between the other panel paintings, with their allusions to subatomic energy fields, and the Near Earth Object series on paper which seem to depict “floating objects” —— “objects” which don’t float so much as emerge from fogged over fields like a detail from a forgotten memory.

Initially, Volatile Compound, at 20 by 22 inches, presents itself as a planet-like form occluded by clouds. But like some crazy Rorschach blot, the form continuously morphs from a flat patterned ellipse to an ovoid, to paired fetuses, to fungus-engulfed egg, to an aperture through which can be seen some kind of electromagnetic field. And the “clouds” which, too, change from misty to flat and textured, seem to reveal a “sky” that looks like a ‘50’s textile. But the variable ultramarine shapes are actually painted on top of both the clouds and the form, and upon this perception, they become fin-like appendages to the ellipsoid.

Layering is the obvious key to Walker’s transformations. The advantage of Walker’s paint of choice, acrylic, lies in its ability to be quickly applied in translucent layers. Building up her image, the artist is combination surgical scrub nurse and tattoo artist, continuously mopping up puddles of half dried paint that she has randomly poured and tilted to form drips, and then carefully filling in the dried edge of a spill with a different colored puddle. Walker employs layers not only physically, but metaphorically, too. The pleasure in viewing her work lies in the constant perceptual shift induced by competing interpretive fantasies.

Walker challenges abstraction’s canonical values of flatness, simplicity, and suspicion of control. She evokes an alternative historical lineage for herself which, in contrast to that of many of her peers, starts with cubism and references important artists that have also rejected status quo painting, such as Al Held.

Walker has adopted many of Held’s abstract pictorial strategies, such as creating space by recognizing that diagonal lines, trapezoids, and ellipses can have a dual pictorial identity—–these lines and shapes can be both flat and spatial simultaneously. And also that negative space can be transparent or opaque depending on what it reveals or conceals.

Walker also shares with Held a similar reference to classical architecture as evinced by an etching of the Pantheon she keeps on her studio wall. But though Walker’s paintings are as complex as Held’s, her work is intimate both in scale and feeling. But unlike Held, her universe is discontinuous and hints at a disturbing irrationality at its core.

With Walker, the most contentious painterly issue is control. She vacillates between wanting the paint to behave in a natural, fluid way and dominating the hell out of it——alternating painting personas of Cinderella and her evil stepmother. Part of this results from her desire to preserve elements of every successive layer she uses, which she has amusingly attributed to her upbringing in the households of hoarders.

The resulting visually complex surface invariably strikes an anxious note for many viewers. But managing information overload has become our contemporary condition and Walker masterfully structures these paintings both physically and metaphorically to accommodate fickle attentions spans. But whenever complexity threatens to overtake her painting she fogs over the offending areas with her painterly equivalents of Klonopin, so we can relax and prepare to be sucked in once more.