June 12, 2015

Editors' Roundtable

In thinking about what makes abstract painting exciting in the 21st century, I keep returning to the phrase "non-gravitational multidirectional space," which Al Held was fond of using in reference to the pictorial organization of his turn-of-the-millennium paintings. Indeed, when we see what is out there in today's global art scene, there is actually a significant amount of exemplary abstract painting characterized by a kind of energetic combustion that moves within and without a painting in multiple directions. Images float or rotate before our eyes. Colors pop. Trajectories intersect, overlap, spiral, and reverberate. Such paintings are demonstrably inviting, and seem almost audible in their inherent ability to call out to the viewer. And with their ultra-luminous palettes, they share a color intensity that is almost as bright as a computer monitor, and thus seems well suited to the digital age.

To my eye, some of the best practitioners of this type of viscerally engaging work are among those I selected for the exhibition (San Antonio Museum of Art, 2010) and more expansive book, "Psychedelic: Optical and Visionary Art since the 1960s." A number of these same artists, as well as others well deserving of attention, were included in the splendid exhibition "Beauty Reigns: A Baroque Sensibility in Recent Painting," organized in 2014 by Rene Paul Barilleaux for the McNay Art Museum and recently on view at the Akron Art Museum.

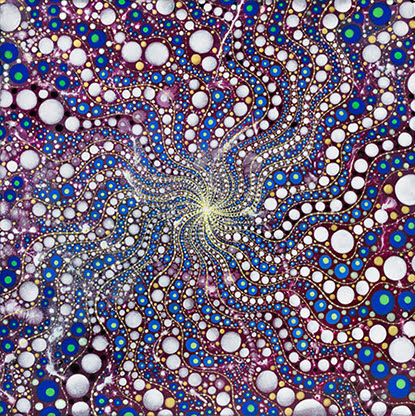

Among the first artists of this genre to emerge in the early 21st century is Barbara Takenaga, who for more than a decade has been producing dazzling abstractions, many of which are executed on a tiny scale, yet yield viewer experiences that are at once enchanting and magical. Based on intricate mathematical systems, Takenaga's paintings owe a debt in part to Yayoi Kusama's dotted works, Fred Tomaselli's night spectacles and the best of 1970s pattern painting. Yet she has created something that is uniquely personal and which eschews the flatness of works by her predecessors in favor of a deeper and more active space. Built up from obsessive renderings of vortex patterns, pinwheels, and cosmic particles set in kaleidoscopic motion, her paintings invite us to move through their space on playful metaphysical journeys, where time has no bounds and lights sparkle with crystalline intensity.

A fascination with hallucinatory worlds and mystical belief systems has in fact been the very starting point for the abstractions of the Venezuela-born artist Jose Alvarez, whose early performance art endeavors involved impersonating a psychic to raise questions about magic and paranormal phenomena. In his painted collages of the past decade, Alvarez combines mandala and floral motifs with ritualistic materials such as crystals, mica, feathers, porcupine quills, and sequins, all of which float suspended within luminescent color fields that are saturated like those in the late-60s paintings by Jules Olitski, though Alvarez' are more vivid and polychromatic. Whether Alvarez' art turns one into a mystical believer or not, it may be enjoyed in aesthetic terms for its consistent vibrancy and uplifting temperament.

In the recent paintings of Susan Chrysler White, interwoven networks of boldly colored lines and planes are punctuated with symbolic medallions and prismatic windows that function like black holes opening up on torrid images of global warming or natural disasters. Inspired by the complexities of the 21st century in all its physical, emotional, and psychological manifestations, White's maximalist paintings are constructed from numerous layers of acrylic and enamel paint applied to glassine paper, which is cut and collaged to canvas. In joining together references from the worlds of art, science, spirituality, and everyday life, White gives us much to digest and consider. At the same time, White's paintings point to the fact that there is really only one visual language that encompasses abstract to representational and everything in between. Whereas Clement Greenberg's championing of flat abstraction in the 1950s and 60s led to a war between opposing camps devoted to two- and -three-dimensional aspects of painting, White proves to us instead that there is much to be appreciated in their healthy unification.

Barbara Takenaga, "Untitled (magenta 17 squared)," 2014, acrylic on paper, 17 x 17". Courtesy of Gregory Lind Gallery, San Francisco.