September 30, 2012

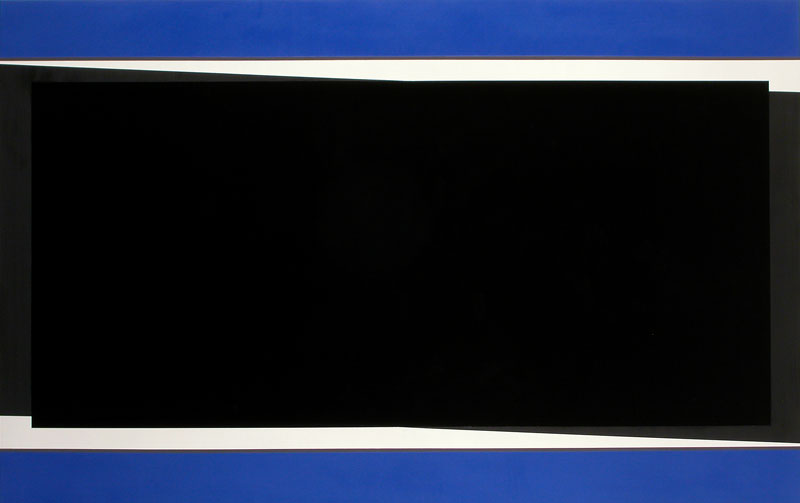

Redacted, 2012

oil on wood, 35 x 55"

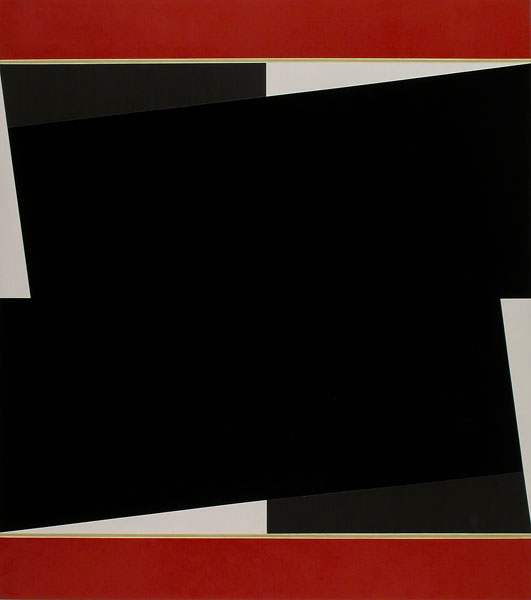

Red Cog, 2012

oil on wood, 36 x 32"

Don Voisine @ Gregory Lind

How to account for the enduring vitality of geometric abstraction a century after its debut? For clues, look to the work of Brooklyn-based painter Don Voisine. His work is a prime example of how contemporary artists mine the past to invent the future. Over several decades, he's shown how squares, circles, rectangles and triangles can be endlessly subdivided and reconfigured. In so doing, he's carved out a unique niche, identifiable by dark heraldic forms set at odd angles interpenetrated by still other off-kilter geometric forms.

While there's plenty in Voisine's precisely executed, color-accented paintings that links him to past masters (from Malevich to McLaughlin) and to contemporary practitioners (like Stephen Westfall), the feature that distinguishes him is theatricality. Admittedly, this is an odd characteristic to ascribe to hard-edged abstraction, a style best known for cool formalism. Yet when I look at Voisine's panel paintings and their taped-off lines, I'm reminded not so much of other painters, but of other media: of screens and stages and, more specifically, of Hiroshi Sugimoto's famous movie theater photos in which long exposures turned the screens white and left the interior architecture of the theaters dimly visible.

Voisine's works, like Sugimoto's, depict the void. They are composed of alternating layers of matte and glossy pigment laid down in close-hued shades, ranging from black to brown to dark gray. You can see "into" them, but only so far. That "limitation" is really a jumping off point. Each of these modestly scaled paintings, which range in size from 12" x 12" to 35" x 55", is bounded on two sides by bright-colored stripes, most of which run horizontally.

But rather than constrict perception, they open the paintings up, enlarging the amount of space they command by imparting the feeling that the central forms - as well as the stripes themselves - extend far beyond the edges. Included among these forms are obtuse black monoliths, like those seen in Richard Serra's oil stick drawings; deformed crosses; and "rivers" whose irregular contours look as if they were cut with a razor and a straight edge. The muscular energy they give off comes from the confusion of positive and negative space, where white and black shapes intersect.

Constructivism, Minimalism and Finish Fetish are just a few of the art-historical styles brought to mind by these paintings. As if to bridge the apparent chasms and to stake out his own territory, Voisine assigns deadpan titles (Sprockets, Slide, Scull, Redacted, Mill, Chamber, Scene) to his works that mimetically describe their contents. Each is a delicate balancing act. Like architecture, where the smallest alterations in form, color and placement can have make-it or break-it consequences, Voisine's works, which are clearly the products of hard-won experience, tread a fine line - between concrete forms we can see and things we can scarcely imagine.