November 7, 2013

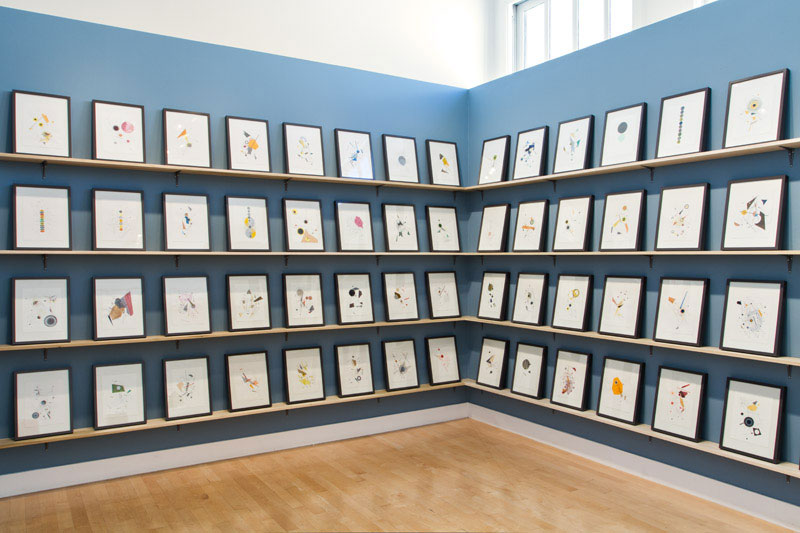

The Library of Abstract Sound, 2013, Ink, gouache, graphite and sometimes collage elements, 11.25 x 8.5in.

Detail: The Library of Abstract Sound

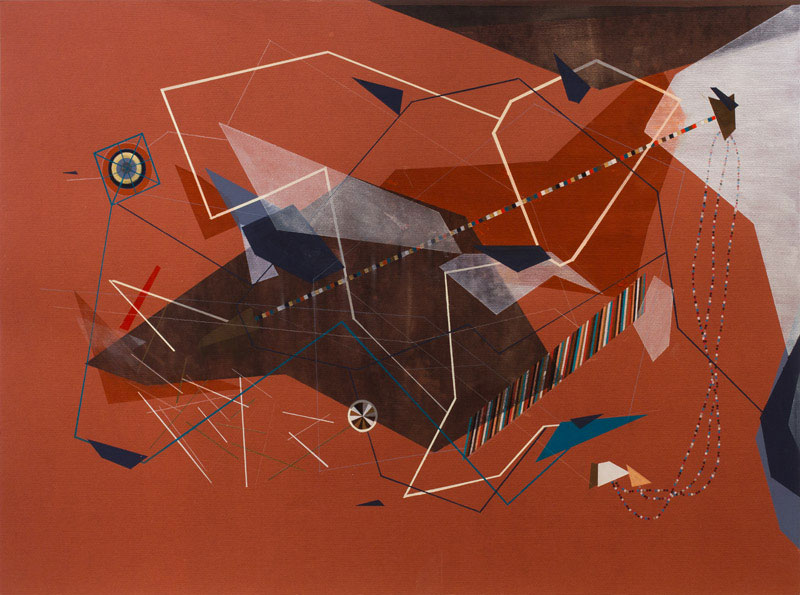

Junillever, 2013, Gouache, ink, colored pencil, graphite and pastel on paper; 27.5 x 39.5 in.

Fanotech, 2013, Gouache, ink, colored pencil, graphite, and pastel on paper; 27.5 x 39.5 in.

Dannielle Tegeder @ Gregory Lind

Few portions of art history have been reframed as many times as early Modernism. Never mind that a century has passed. The potent visual vocabularies of Constructivism and Suprematism continue to excercise an outsized influence on contemporary painting, particularly on those parts that lean toward hybridity. Such painting, also known as Abstract Conceptualism, can be maddeningly referential; much of it points everywhere and nowhere, often with too few real-world guideposts. Success, therefore, necessarily depends on who's doing the reframing.

New York artist Dannielle Tegeder does a fine job of it. Her geometric drawings - made of vectors, overlapping planes, odd shapes and transparent volumes that run off the edges - appear, at first glance, to be homages to El Lissitsky, Malevich and Kandinksy. But they are much more. To understand why, you need to see a large exhibit of her work because each element of her multi-faced oeuvre - which includes drawing, painting, wall installations, mobiles, video and freestanding sculpture - is designed to work in tandem. One such event took place last spring at the Wellin Museum in Clinton, New York. There, Tegeder demonstrated, among other things, that space is an elastic notion: extensible in two or three dimensions, possibly four if you count sound. Within those realms she moved easily from intimate drawings to wall-sized installations, as if translating ideas into objects involves only the projection of mental energy, not physical problem solving. Happily, a copy of the exhibition catalog is on view in the gallery. It gives context to the vastly reduced (but representative) sampling of the work seen here.

The exhibit's main feature, apart from four medium-sized drawings, is an ambitious installation called The Library of Abstract Sound, which is also the show's title. It consists of 86 small drawings displayed on four shelves accompanied by sounds that derive from the drawings themselves. The artist scans them and feeds the information into software that converts shape into sound - or sometimes, like Cage, into silence - depending on the amount of white space. The "compositions" range in length from 20 seconds to several minutes - nearly seven hours worth in its original version. The resulting "music" - digitally assembled from real instrument samples - ranges from quirky Minimalism to something akin to '50s chamber jazz. It purrs at a low volume from a video monitor that shows electronic versions the drawings being created in the manner of a stop-animation Etch-a-Sketch. If you look long enough and listen closely you can begin to visualize shapes from having heard the corresponding sounds. Or so the thinking goes.

The idea, as it happens, was Kandinsky's. He experienced the intermingling of sensory information known as synesthesia, whereby input from one sensory source seeps into another, as in "tasting" sound or "hearing" color. Kandinsky tried to map the idea by including musical figures in his drawings. But he took it no further. And apparently, neither did anyone else until Tegeder gave it a shot. Whether she succeeds or not is difficult to say. It could take hours, days, weeks or even months of exposure to really know.

Individually, the drawings that comprise Library more than carry the load. Color is applied sparingly to basic forms: concentric circles and irregular geometric shapes that are connected by thin pencil lines. Some are drawn directly on the paper; others are collaged. The compositions, while precisely balanced, have a provisional feel, as if the elements were interchangeable, modular. But, as with everything Tegeder does, the suite takes on power when viewed as a collective whole, not as a series of discrete compositions. The same holds for the larger drawings. They employ the same forms, but appear on grounds of solid, strong colors - colors that by all rights should influence our emotional responses, but don't. Instead, we're struck more by how the shapes interact, with how lines move through space and swerve into riotous, cubist clusters or disappear into irregularly shaped solids. Overall, these are spooky pictures. They speak of an underworld, of things concealed yet palpably real.

The source of that reality can be found Tegeder's biography. She comes from a long line of steamfitters - professionals whose job is to design steam- and water-conveyance systems for buildings. Blueprints were the backdrop to her childhood, and her plan, before she took up art, was to join the family business.

Thus, it's no surprise that her works point to hidden infrastructures. They allude to not only physical things, like pipes and ducts, but also to virtual entities like data networks, fiber optic connections and to the less-easily grasped notion of "the cloud". This complexity points to major differences between Tegeder and her sources. Where the Constructivists (and the Greenberg-influenced formalists who came later) were attempting to reduce art to vital essences, today's Abstract Conceptualists are trying to do the just opposite by visualizing complexity, multiplicity, hybridity. Tegeder's titles, which I've abbreviated, say as much. Example: Noando: Rosa Crystal Code, with Covert Machine Explosion, and Synthetic Ruby System, with Headquarter Results and Lower Level Capsule Rooms, Sideway Half-Circle Tower Housing with Central Housing and Color Coded Grid for Population Expulsion.

In this endeavor she has company. In New York there's Kristin Baker and Julie Mehetru. In the Bay Area, we have Robert Ortbal and Val Britton, and in Southern California, Alex Couwenberg uses a visual language similar to Tegeder's to describe landscape. Unlike her peers, Tegeder recognizes the impossibility of conveying the kind complexity she envisions in any single work of art. Hence, the interdependency of the drawings seen here and the multi-media approach she took at the Wellin.

Looking at this show reminded me of when I used to stare at Manhattan from the Brooklyn waterfront and wonder: how can all of this exist? I was imagining the maze of interlocking systems that allow a city to function. I imagine Tegeder having many such thoughts. Her art doesn't answer my question, but it certainly gives shape to it. Many shapes, in fact.