June 24, 2015

Phillip Maisel @ Gregory Lind

Palomar Mountain, (0928) and (0930), 2015, archival pigment prints, each 22 x 18.3”

Feldspar (1101), 2015, archival pigment print, 21.5 x 18.7”

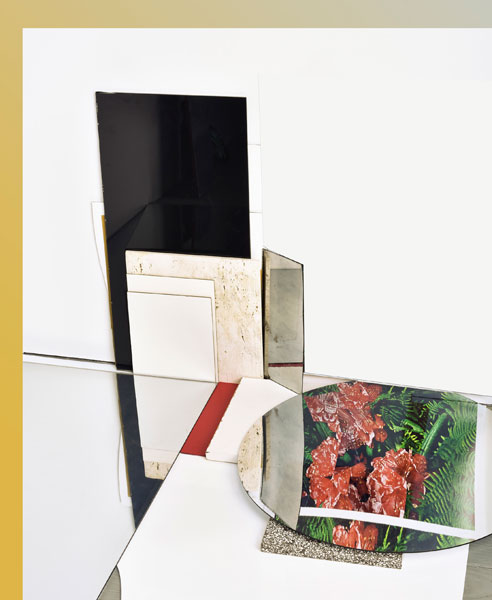

For a young artist who only just graduated from the CCA MFA program a couple years ago, Phillip Maisel, in his exhibition The Perfect Copy, is off to an impressive start. With a combination of sculptural assemblages and photographs of similar assemblages made in the studio, Maisel has carved out a unique space for himself. His work consists of photographs of pieces of colored or mirrored plexiglass, wood and other materials propped up against a studio wall. The results tend to resemble Constructivist paintings both in their palette and rectilinear compositions.

The images fall somewhere between setup photography and geometric abstraction, and as such they can be viewed as either flat, semi-abstract compositions or asarrangements of objects. But several characteristics argue against such easy readings. These include the frequent use of mirrors, a careful formalization of the arrangements and modifications to the surfaces of the prints themselves. As a result, we engage with his work by mentally translating the fragmented pieces back into what they once were, retracing the process by which they were composed in the studio. Likewise, you might also notice that certain seamlessly integrated shapes were, in fact, added at later stages of production — during the editing process or directly onto the surface of the print.

In Feldspar (1088, 1091, 1094), what appears to be a continuation of a red rectangular shape is actually part of a separate overlapping print. With Feldspar (1101), it takes longer to realize that one area of the print is actually a reflection of unseen materials. They were collaged over and obscured, the result being a reflection with no visible source. These effects are subtle, but they carry a lot of weight. In Feldspar (1095), for example, a black trapezoid reveals itself to contain a faint reflection, so that what at first looks flat turns out to have spatial depth, a faint echo that, once apprehended can knock you back on your heels.

Maisel isn’t alone in these pursuits. Other artists working this territory include Yamini Nayar and Carter Mull. Their work is generally more flamboyant than Maisel’s, which, by comparison, is spare and quiet. In that regard it has more in common with Anne Collier’s photographs: works in which the tension between surface and set-up is carefully calibrated and asserted.

Maisel’s sculptures aren’t nearly as effective as his photos. They consist of collections of randomly sized plexiglass and rectangles of wood resting on the floor like accumulated studio detritus. With some exceptions they do little more than function as props for the photographs. The best one, however, is nestled between a wall and a flat file. It is so unassuming that it barely registers as part of the show. Once it does, it activates the same dynamic as the photos, showing us a single gridded sheet before revealing itself to be comprised of multiple layers of plexiglass.

Maisel’s most successful images appear in a grouping of six works, each titled Palomar Mountain. They’re hung in a tight grid, their primary colors standing out in sharp contrast to the staid grey-and-yellow Constructivist palette seen elsewhere. Densely layered and more variously weathered and patterned, they operate as a multi-part composition, a bit like the works of Bernd and Hilla Becher where repetition accentuates minute differences.

There’s a greater degree of obfuscation in this sextet, too, which in turn, gives way to something more arduous and convoluted: a contemplative yet analytical engagement hovering at the edges of confusion. As with certain kinds of puzzles, the pleasure of finding the solution increases with the difficulty, and the process transcends the goal. With a few simple tricks up his sleeve, Maisel encourages us to engage actively and then, through a gradual multiplication of compositional complexity, escalate our level of involvement. In doing so, he encourages a mode of proactive seeing in which looking and thinking closely intertwine.

–ELWYN PALMERTON