![]()

August 11, 2011

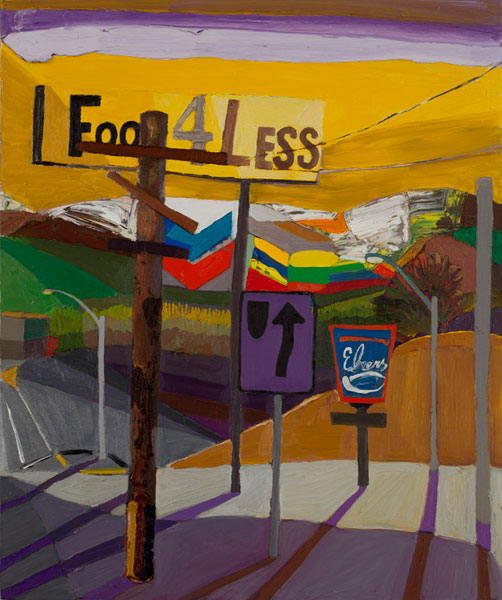

“Food 4 Less I 5,” by Karla Wozniak, at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, part of “Bronx Calling: The First AIM Biennial.”

Learning About the Marketplace and Entering It

In a metaphorical land not far from reality, a beautiful palace rises from a desolate plain of want and envy. It is surrounded by an invisible but impregnable wall and a moat full of sharks and crocodiles. Inside, successful artists work in spacious, light-filled studios and dally in sensual pleasures.

Outside the wall and the moat, thousands of haggard, hungry, unsuccessful artists have gathered to stare longingly at this unreachable Xanadu. They plead for admission. They scheme, bargain, trade possible passwords and vie with one another to hold their paintings and sculptures up above the throng, hoping against hope that they will be spotted by someone inside and invited in for the big dance.

This may sound fanciful, but there is enough truth to it to have prompted programs granting master of fine arts degrees across the real America to institute courses in how to make it in the art business. No one graduates these days without a seminar on preparing to operate and advance a career in pragmatic, properly professional ways.

There are programs for those who have finished school too, like Artist in the Marketplace — a k a AIM — which the Bronx Museum of the Arts sponsors. Every year over the past three decades, the AIM program has selected a group of hopefuls to take part in a 13-week seminar introducing them to the ins and outs of the market and the artist’s place in it. While continuing to make art, they meet with established artists, collectors, critics, curators, dealers and lawyers, and they learn about exhibition opportunities, galleries, grant writing, copyright law and income tax. Then they all display their work in a big group show, which until now was held annually. Beginning this year, it will take place every other year; hence the subtitle in “Bronx Calling: The First AIM Biennial.”

All 72 participants in the 2010 and 2011 sessions are included, and their creations are on view at the Bronx Museum of the Arts and in the indoor galleries at Wave Hill, the public garden and cultural center. (Outdoor works — not under review here — also will be part of “Flow.11: Art and Music at Randall’s Island.”)

The AIM exhibition is not to be taken as an indicator of the program’s value. What the participants learn will be revealed later in ways that may or may not be easily observable or quantifiable. It is worth noting, however, that while most of this year’s aspirants look ready to show at a starter gallery somewhere, the next Jeff Koons or Ryan Trecartin does not appear to be among them.

But there are some who will warrant keeping an eye on. One for sure is Jessica Stoller, who creates exquisite, tabletop-scale, glazed porcelain figurative sculptures. They mimic grandmotherly tchotchkes, but a closer look discovers a surrealistic play with bodily abnegation. One is a head of a woman with thick red hair whose nose has been cut off; gold-glazed liquid drips from the orifices. Another portrays a figure with two tortured heads, one male and one female, who wear intricately worked, lacy blindfolds. Ms. Stoller mixes beauty, horror and dark comedy with a fine sense of proportion. (Her sculptures are only at Wave Hill, which has the better selection and presentation of artists.)

Other works at Wave Hill include Matthew Conradt’s large, vaguely nightmarish collages picturing faceless figures in Cubist-Surrealist compositions, and wooden sculptures by Romy Scheroder, in which parts scavenged from found pieces of furniture are joined into oddly dysfunctional constructions.

Among outstanding efforts at the Bronx Museum are works by Laura Braciale, who creates oversize versions of drafting tools in two and three dimensions that recall the early, Pop-realist sculptures of Vija Celmins. A painting on canvas reproduces with a slightly cartoonish touch a small, gridded, green-on-green panel used for measuring angles that is displayed just around the corner.

Erik Hougen’s big photorealist watercolor portraits of different men owe too much to Chuck Close, and the trails of colored drips running through them are an annoying affectation, but they have a persuasive technical ambition. Julia Oldham’s video of herself and her double in dreamy meetings supposed to allegorize something about small-particle physics is expertly produced and psychologically intriguing.

Karla Wozniak’s pictures of pastoral landscapes blighted by roadside signage are made in thick, crusty patches resembling colored concrete; they combine Cubism and Pop with satisfying, painterly punch. Thomas Bangsted’s dark seven-foot-wide photograph of a private tennis court is formally assured and hauntingly atmospheric. And Andrew Chan’s papier-mâché and wire sculpture of a much enlarged, woozily misshapen shopping cart has a Red Groomsian comic verve and a good title: “Magna Carta.”

Exceptions like the foregoing aside, most of the work is nondescript and routinely derivative. So you can’t help wondering if programs like AIM are promising something that they cannot deliver. No amount of knowledge about how the art world works and no pragmatic tool kit can substitute for uncompromising drive, singular imagination and personal charisma. An art career is not like any other; you have to be a little crazy to make a serious go of it.