May 17, 2015

Tom Burckhardt’s Arrival

by John Yau

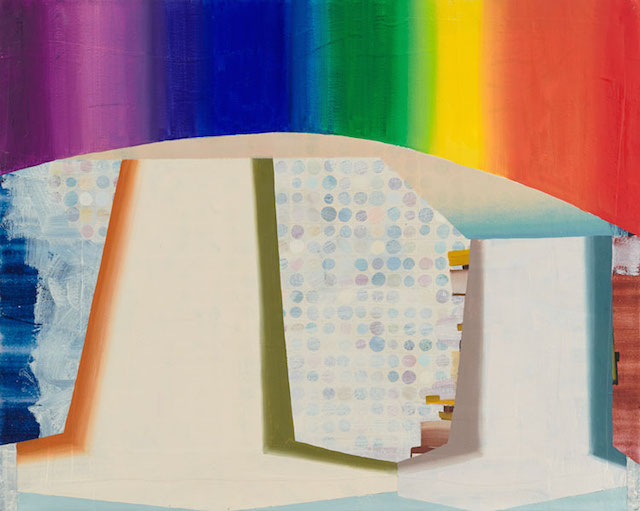

Tom Burckhardt, “Incognito” (2013),

oil on cast plastic, 32 x40 inches (all images courtesy Tibor de Nagy)

Tom Burckhardt, “Three Ninety to Seven Eighty” (2014),

oil on cast plastic, 32 x 40 inches

Tom Burckhardt, “Odalik” (2015),

oil on canvas, 48 x 60 inches

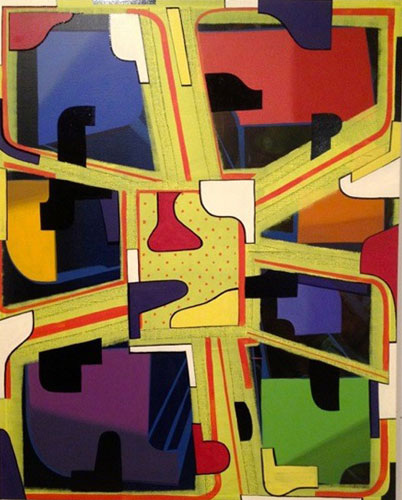

Tom Burckhardt, “The Incredible Think” (2015),

oil on linen, 48 x 60 inches

Tom Burckhardt, “Tangential Meditation” (2015),

oil on linen, 60 x 48 inches

Tom Burckhardt just keeps getting better and better. In his most recent exhibition, AKA Incognito at Tibor de Nagy (May 7–June 12, 2015), there are two kinds of paintings: one group is done on cast plastic supports, with the largest ones measuring 32 x 40 inches; the other, larger in size, is done on canvas, including a recently completed two panel painting, “Gunung” (2015), which measures 60 x 96 inches.

By pairing the two kinds of painting under the show’s title, AKA Incognito, suggesting that something is in disguise, Burckhardt introduces an element of doubt and humor into our experience of the work: are the ones on plastic pretending to be real paintings? Does this mean the ones on canvas are real? Or are they both real and fake? In an age of rip-offs, copies and fictional memoirs, what do real and fake even mean? Burckhardt underscores these contradictions with sharp titles, such as “Schmeary Theory” (2014) and one of my favorites, “Sacrediculous” (2015), which pretty much sums up how a painter might be feeling these days. If he weren’t such an imaginative, adventuresome, and interesting painter, who has been steadily moving further and further into his own territory, the whole thing could seem hokey or, worse, didactic.

The cast plastic supports are thick and boxy. Burckhardt paints fat black dots on the sides suggestive of nails holding down stretched canvas, while the surfaces are uneven, as if the artist has affixed torn strips of cloth on them, like bandages. On some level, the ‘bandages’ evoke the works of the great Alberto Burri, who made a textured canvas out of burned plastic. Historically speaking, coming after Burri and others, Burckhardt recognizes that he is painting on the bandaged surface of an irreparably damaged thing; more importantly, he accepts his position in this chronology rather than emulating the past.

In an interview I did with the artist in The Brooklyn Rail (April 2011), he characterized his cast plastic supports as “kind of like a representational sculpture.” He went on to say:

I really love painting, but I also want to make fun of it. I want to have that full range of experience. I don’t want to be a true believer, and wear blinkers about it. I want to acknowledge its absurdity, that’s the thing.

It is in the painting itself that Burckhardt, who was born in 1964, distinguishes himself from other abstract artists of his generation. Rather than relying on a particular or signature process, vocabulary, message or aesthetic justification (which is what “provisional painting” has predictably become), he discovers the painting through what can only be called trial and error. He introduces an image into the work, overlaps it with something else, covers nearly everything over and starts again. While one sees the evidence of earlier stages peeking through many of his paintings, Burckhardt doesn’t fetishize his pentimenti. He isn’t trying to impress the viewer with his labor, which, like watching a weightlifter having to prove how much he can hoist in the air, quickly proves tiresome.

Academic discourse, at least the kind you are apt to come across in the pages of journals such as Artforum, is about turning art into quantifiable meaning, an aesthetic sticker announcing political and aesthetic affiliations. Perhaps the most overt sign of Burckhardt’s resistance to the incursions academic discourse has made in art is in the title “Schmeary Theory.” I think there is something delightful and disturbing about looking at something that you cannot name, that in fact resists any attempt to corral it in simple, commodifiable language. And there is something even more delightful if a name is on the tip of your tongue, then suddenly seems light years away. At the very least, you might be reminded that even if you can afford to possess something, you cannot fully own it, which I think is worth remembering.

Only someone who is conversant with art history can present ambiguity with such graphic clarity and painterly precision. In the humorously titled “Odalik” (2015) — a sonic combination of “odalisque” and “lick” — the white tubular form that extends down the painting’s left side and along the bottom edge, before rising slightly on the right side, is a descendant of such reclining nudes as Titian’s erotic “The Venus of Urbino” (1538) and Manet’s harshly lit painting of a prostitute, “Olympia” (1863). Burckhardt’s “nude” seems to be made of a continuous brushstroke that keeps reversing its direction. It’s a fiction, of course, because no single brushstroke could remain so even and continuous, making Burkhardt’s nude look like a length of white tubing discarded on a factory floor, and in this regard it is also related to the “bride” in Marcel Duchamp’s “Large Glass” and Francis Picabia’s mechanical portraits.

And yet, for all its reverberations, Burckhardt’s white abstract form doesn’t come across as either a parody or citation. It is a white tubular form that is both redolent and chilly, reclining in front of brown shapes whose diagonal alignments suggest that they are receding in space. In their outline and palette the brown forms resemble benches or church pews. The black ground is punctuated by grid of diagonally aligned white dots, which can be read as either a night sky or printed fabric. Through articulation, placement, color choice, and a vocabulary of discovered forms, Burckhardt connects his painting to a long and distinguished tradition. The fact that it holds it own is a mark of his burgeoning mastery.

In “The Incredible Think” (2015), Burckhardt’s placement of a reddish band with diagonal struts along the painting’s top edge suggests the stretcher bars of a painting. Are we seeing through the stretcher, or are we looking at the back of a stain painting? What about the form in the foreground, which is made of colored rectangles outlined in black, most of which are a shade of green? Is it an escapee from Michael Bay’s film Tranformers (2007)? What about the building-like facades behind and below the robot-like structure?

In the large paintings, Burckhardt plays with the various conventions governing such genres as landscape and the figure in a landscape. The space is made out of layers that run from opaque to semi-transparent. He can combine different forms, lines, patterns, and gradated colors, as he does in “Tangential Meditation” (2015), into a solid but unidentifiable object, with recessed spaces divided into light and shadow. Nothing feels extraneous or overly elaborate.

Burckhardt doesn’t repeat his palette and he applies the paint in a variety of ways without making a big deal out of it. The mastery is understated, but it should be evident to anyone who slows down long enough to begin looking at the work. These paintings invite prolonged scrutiny, in which part of the pleasure is seeing how the artist has fitted disparate things together. They are as intricate as the interlocking, overlapping gears of a pocket watch, and as magical.