![]()

March 30, 2011

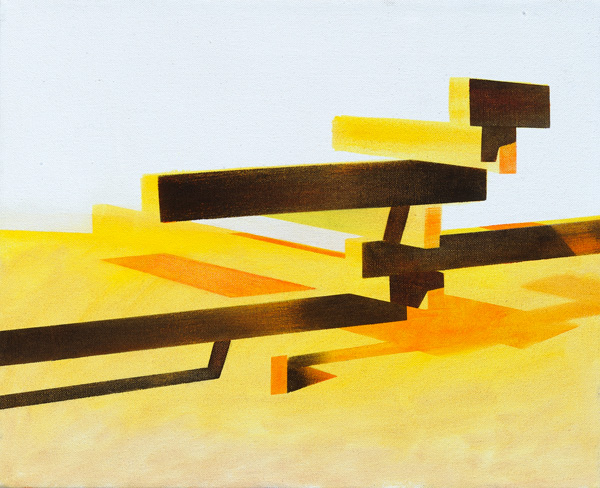

WILL YACKULIC, CLAYPOOL'S, 2011, COURTESY OF GREGORY LIND GALLERY

Exercises in style

by Matt Sussman

HAIRY EYEBALL Will Yackulic's return to painting has none of the grandiosity or pretension that the phrase "return to painting" might suggest. Rather, Yackulic's abstract canvases at Gregory Lind offer a contained (one might say modest, even, as each rectangle measures in the neighborhood of 144 square inches) but no less exhilarating exploration of the tension between the two qualities of his work that are so perfectly pinpointed by the show's title, "Precision and Precarity."

Although it has been six years since Yackulic last picked up a brush, his approach here is not unlike the works on paper he has steadily created in the interim. Much like his wave fields made from the dense accumulation of precisely spaced typewriter keystrokes, there is a finessing of the medium in this new group of (mostly) oil paintings that never claims mastery. The material seems to have had as much of the final say as the artist's hand.

The subject of the conversation — geometric abstraction — has been a recurring one for Yackulic. This time, instead of floating geodesic orbs, the starting point was a Jenga-like stack of woodshop scraps Yackulic constructed and then set about capturing using a variety of colors, paint application techniques, perspectives, and degrees of abstraction. One canvas, the appropriately titled Smolder, even appears to have been burnt with a cigarette.

Some paintings come across as proper still lifes, engaging with the woodpile as a physical object. Taken together, the heavy yolk-yellow highlights and brown shadows of Claypool's and the nocturnal blues and watery purples of Crepuscular and Evening Arrangement form a dance of the hours played across what could be a model of one of mid-20-century architect Joseph Eichler's experiments in suburban modernism.

Other canvases respond to the form as a prompt about pure shape, discarding fixed dimensionality. In Over/Under, jutting lines become breakwalls for an incoming tide of indigo that has spilled over into the canvas' azure lower half. Yackulic also employs other shapes (the cross-hatches in XXXX, the Easter-ish green and pink dots of Sick Day) to colonize what becomes, over the course of the show, familiar terrain.

All this shape shifting brings to mind Raymond Queneau's Exercises in Style (1949), in which the experimental French writer retells the same banal incident 99 times employing a different voice, genre, or formal device with each successive iteration. Yackulic does much of the same thing in "Precision and Precarity," only the story he's retelling is the abstract tradition in modern art.

Retelling, though, shouldn't be confused with repeating, and Yackulic doesn't shy away from giving his exercises in style some bite when necessary. The aforementioned Smolder, although hung closest to the gallery's entrance, provides a humorous coda to the rest of the show. Slanted lines, suggestive of the beams of Yackulic's original model, disappear into a black cloud of pencil smudge as if to playfully say, "You know what else depends on precision and precarity? Arson."