December 19, 2013

Jake Longstreth’s Beautifully Dissonant, Monastically Simple Landscapes

by Scott Indrisek

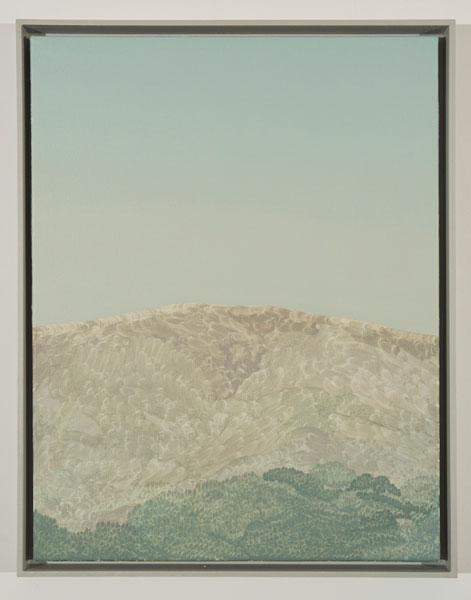

Need an antidote to flash and spectacle? Jake Longstreth’s current painting show at Monya Rowe Gallery is a good place to start: A series of monastically simple, refined mountain landscapes, all variations on a theme, most of them a modest 19 by 15 inches in artist-designed frames. The brushy gestures of rock and foliage butt up against gradient-faded skies.

“The landscapes are imaginary, though they draw upon a lifetime of memory and impressions,” says Longstreth, whose studio is in Los Angeles. (And yes, he’s the brother of David – crooning mastermind behind the Dirty Projectors – proving that the Longstreth family is indeed an uncommonly talented one.) “I thought that modestly scenic places choking under harsh atmospheric conditions would be an interesting way to approach paintings of pure landscape. Maybe ‘choking’ is too intense a word – the paintings live and die in their subtlety – but the effort was to show landscapes that marry the very plain and ordinary with a very sour, creeping dissonance.”

“The paintings are an amalgamation of places I’ve been in and observed over time,” he continues. “They might derive from things seen backpacking in the Sierras, or a momentary glimpse of a ridge line behind a Home Depot. Years ago I tried making paintings of natural landscapes from photos and from working on-site; the results were stale and literal. So I started working from memory. I don’t want the paintings to read as fantastical though – it’s important to me that they ride the line between being perhaps a credible depiction of a real place and a highly synthetic abstract painting.”

Of course, L.A.’s rough mix of environments – city and nature thrown together, all beneath a warm blanket of smog – likely had an influence on the compositions. “Los Angeles is a place that tethers between the brutally urban and the idyllic in its own weird, unique way,” Longstreth says. “I’ve always been compelled by the lay of the land here. It’s simultaneously lovely and harsh, verdant and dry, and it doesn’t feel as anachronistic as you might think making the mountain paintings here.”